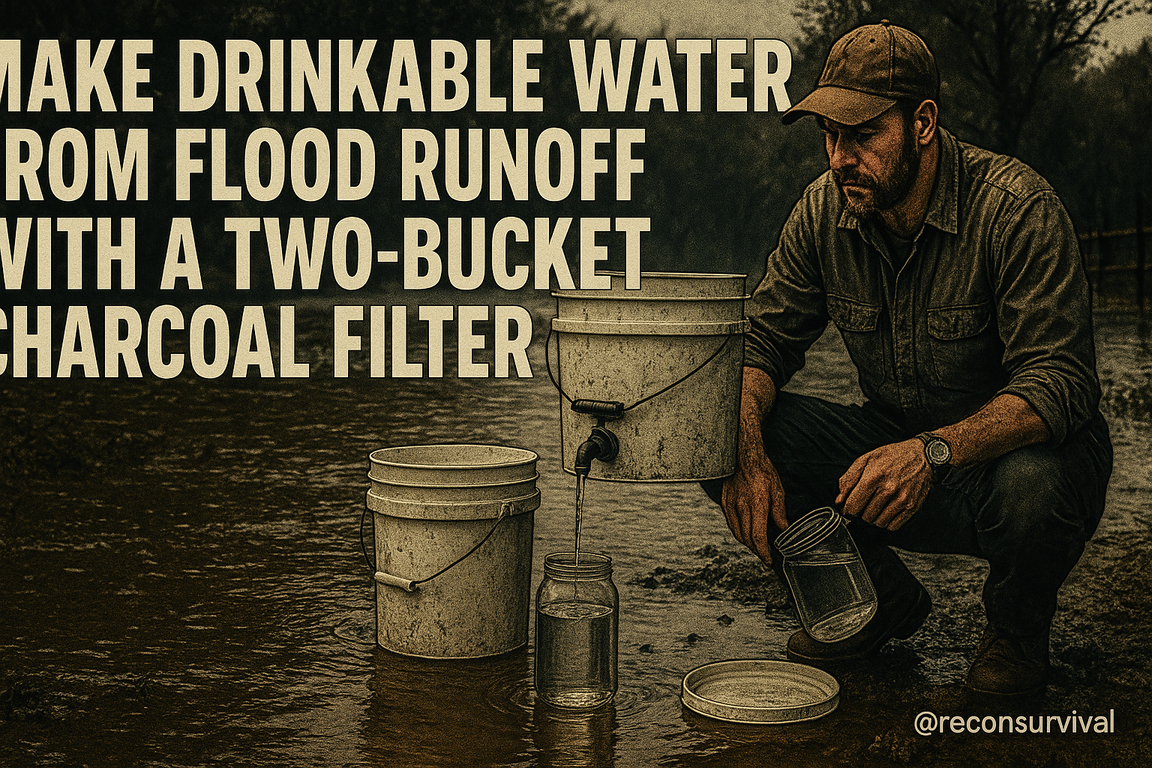

The flood has slipped back into the riverbed, but your kitchen tap still coughs air. The store shelves were stripped two days ago; the tanker trucks are “on the way.” Meanwhile, every puddle in sight is the color of coffee and smells like a fuel depot. Post-flood testing routinely finds sewage bacteria and chemical residues in surface water—exactly the sort of cocktail that turns a survivable event into a health crisis. You don’t need a lab or a thousand-dollar purifier to bridge the gap. You need two buckets, a handful of common materials, and a method that’s been proven again and again in the field.

I’ve built and taught low-tech water systems for disaster teams and remote expeditions, and the two-bucket charcoal filter is the one that checks all the boxes under pressure: fast to assemble, forgiving on materials, and capable of turning filthy runoff into clear, drinkable water when paired with proper disinfection. It’s not a magic trick—it’s smart physics and chemistry. Gravel and sand strip out grit and microbes by size and surface capture; charcoal adsorbs the odors, colors, and many organics that make flood water risky and unpleasant.

In the pages ahead, I’ll show you exactly how to scavenge the right parts (food-grade buckets, a spigot, cloth, sand, and charcoal you can make on a campfire), how to build the filter so it flows at a usable rate, and why each layer matters. We’ll cover the critical finishing step—disinfection by boiling or bleach—with precise dosing and timing. You’ll get troubleshooting tips for cloudy water and slow flow, realistic performance expectations, field tests that require no lab, and the hard limits (what this system won’t remove and when to walk away). If you need safe water within the hour, this is the blueprint.

From Brown Soup to Safe Sips: What Floodwater Contains and What a Two-Bucket Charcoal Filter Can (and Can’t) Remove

From Brown Soup to Safe Sips: What Floodwater Contains and What a Two-Bucket Charcoal Filter Can (and Can’t) Remove

You scoop a bucket from the curbside torrent after a storm, and it’s not just brown—it’s alive. Floodwater is a stew of silt, shredded vegetation, septic overflow, barnyard runoff, and whatever was stored in garages and sheds upstream. Before we talk buckets and charcoal, know what you’re up against and what your filter can realistically accomplish.

What’s In Floodwater—and Why It Matters

- Biological hazards: E. coli, Salmonella, Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and viruses (norovirus, hepatitis A) from sewage and animal waste. These can be present even when water looks clear.

- Physical loads: Heavy turbidity from clay and silt (often >500 NTU) that shields microbes from disinfectants and clogs filters fast.

- Chemical contaminants: Gasoline/diesel sheen, lawn chemicals, pesticides, and solvents from garages and farm fields. Heavy metals (lead, arsenic) can be mobilized from soil or plumbing debris.

- Nuisance compounds: Tannins and humic acids from leaf litter—harmless but taste like a swamp and consume chlorine during disinfection.

Each category behaves differently. Pathogens and particles can be mechanically removed. Many organic chemicals can be reduced by adsorption. Dissolved salts, nitrates, and most metals? Not so much with a field-expedient charcoal setup.

What a Two-Bucket Charcoal Filter Does Well

A gravity two-bucket filter—sediment layers over a charcoal bed—tackles what you can see and smell.

– Turbidity reduction: Properly packed layers (gravel > coarse sand > fine sand > crushed activated carbon) can take muddy water to clear, often below the ~5 NTU target where chlorine works reliably.

– Adsorption: Activated carbon (500–1,500 m²/g surface area) grabs many organic compounds, improves taste/odor, and reduces petroleum residues. Slower flow equals more contact time and better performance; aim for a gentle drip to thin stream (roughly 0.2–0.5 L/min). Faster flow suggests channeling.

What It Cannot Do (Don’t Bet Your Gut on Carbon Alone)

- Disinfection: Charcoal does not reliably remove viruses and can’t be trusted to eliminate bacteria/protozoa. You must disinfect after filtering—boil 1 minute (3 minutes above 6,500 ft) or chlorinate (per gallon: 8 drops of 5–6% bleach or 6 drops of 8.25%; wait 30 minutes).

- Dissolved inorganics: Nitrates, fluoride, and most heavy metals pass through. If the source likely contains industrial chemicals or obvious fuel spills, seek an alternate source.

Common Mistakes and Quick Fixes

- Using BBQ briquettes with binders: They add contaminants. Use activated carbon or crush/rinse hardwood lump charcoal.

- Rushing flow: If it pours, it’s channeling. Repacks layers tightly and add a cloth prefilter.

- Filtering after chlorination: Carbon strips chlorine. If you need a residual for storage, disinfect after carbon and keep the container sealed.

Key takeaway: Your two-bucket charcoal filter is a clarity-and-chemicals reducer, not a sterilizer. Use it to make floodwater disinfectable and palatable—then finish the job with heat or bleach. Next, we’ll build the filter correctly so it performs when the water doesn’t.

Build From the Bins: Materials, Dimensions, and Safe Sourcing for a Two-Bucket Charcoal Filter

Build From the Bins: Materials, Dimensions, and Safe Sourcing for a Two-Bucket Charcoal Filter

A neighbor’s garage coughs up two “empty” buckets after the water drops. One held frosting, the other pool tablets. Only one belongs near your drinking water. When flood runoff is your source, what you build with matters as much as how you build it.

Materials That Won’t Betray You

- Buckets: Two 5-gallon, food-grade HDPE (#2), with tight lids. Look for “food safe,” “NSF,” or previous contents like syrup, pickles, or flour. Avoid buckets that held chemicals, paint, petroleum, or pool chlorine—residues linger and leach.

- Fittings: One 1/2-inch NSF-61 bulkhead fitting and a 1/2-inch full-port ball-valve spigot for the lower bucket. Choose lead-free brass (LF) or potable-rated PVC/nylon; use EPDM or silicone gaskets and PTFE tape.

- Screens and cloth: Stainless mesh (20–30 mesh) or window screen to keep media contained, plus a tight-weave cloth (unbleached cotton or poly felt) as a prefilter.

- Media: Washed pea gravel (3/8-inch), clean silica sand (play sand or pool filter sand), and activated carbon (granular, 8×30 or similar). If buying isn’t an option, use clean hardwood lump charcoal—never briquettes with binders or anything from treated/painted wood.

Why: Food-grade plastics and potable-rated fittings reduce chemical leaching; the right media and mesh control flow and prevent bypass, which directly affects contaminant removal.

Dimensions That Drive Performance

- Spigot: Drill the lower bucket 1.75 inches up from the bottom (centerline). Typical 1/2-inch bulkheads need a 1-1/8 to 1-3/8-inch hole—check your fitting.

- Layout options:

1) Nested-perforated: Drill 30–50 holes (1/8-inch) in the bottom of the top bucket; line with mesh. It nests into the lower bucket’s lid or lip.

2) Bulkhead-to-bulkhead: Join buckets with a sealed fitting. Better control, more parts. - Media volumes for a 5-gallon top bucket: 1.5 inches gravel, 3 inches coarse sand, 3 inches fine sand, 4–6 inches carbon. Expect 20–25 lbs media total. Target flow 0.5–1.5 L/min; slower improves contact time.

Safe Sourcing in a Messy World

- Where to find: Bakeries, restaurants, deli counters (free/cheap food-grade buckets). Aquarium shops (activated carbon). Big-box stores (play sand, pea gravel). Avoid landscaping gravel or sand from flood zones—unknown contamination.

- Inspect: Sniff for solvents, examine stains, and look for etching. If in doubt, don’t use it for drinking water.

- Note: This filter clarifies and adsorbs—it does not guarantee pathogen kill or remove all chemicals. Plan to disinfect post-filtration (boil, chlorine, UV).

Common mistakes: using briquettes, unwashed sand (instant clogs), brass not labeled “lead-free,” or an ultra-low spigot placement that drains sediment.

Key takeaway: Choose food-safe buckets, potable-rated fittings, clean graded media, and measured dimensions to control flow and contact time. Next, we’ll prep and layer the filter so it works under real flood conditions.

Pre-Treat to Protect Your Media: Settling, Flocculation, and First-Stage Screening for Dirty Runoff

When the floodwater finally drops and you’re standing over a five-gallon bucket of chocolate-milk runoff, the worst move is to dump it straight into your charcoal. You’ll cement your media into a brick in minutes. Pretreatment isn’t optional—it’s how you keep flow rates up and extend the life of your two-bucket filter from “one afternoon” to “the rest of the week.”

First-Stage Screening: Keep the Big Stuff Out

Start by straining debris before it ever touches a settling bucket. Stretch a 200–400 micron mesh (paint-strainer bag, nylon stocking, or a fine kitchen sieve) over a clean container and pour through. Two to three layers of a tightly woven T‑shirt or pillowcase work in a pinch; rinse them often to maintain flow. This step removes leaves, grit, and glass—things that cut hands and clog pores—without driving fines deeper into your media. Common mistake: pressing or wringing the cloth to “force” water through. That pushes silt through the weave and into your next stage. Let gravity do the work.

Settling: Let Gravity Do the Heavy Lifting

Pour screened water into a settling bucket and fill only to about 75% to leave headspace. If your bucket has a spigot, install it at least 2 inches above the bottom; that gap becomes your sludge zone. Stir vigorously for 15 seconds to homogenize, then cover and let sit undisturbed 1–2 hours (double that if water is near freezing). When a distinct layer of clear water forms on top, decant from the spigot or use a cup to skim without disturbing the bottom. If you must pour, tip slowly and stop as soon as the cloud approaches. Troubleshooting: if you’re outdoors, wind and vibration keep fines in suspension—cover the bucket and set it on soil, not a vibrating porch. Oils or chemical sheens are red flags; don’t process petroleum-laden water through a DIY system.

Flocculation: When Mud Won’t Settle

For stubborn turbidity, add a coagulant. Aluminum sulfate (alum) is compact and reliable. Field dose: start with 1/8 teaspoon per 5 gallons (about 25–30 mg/L). In a small jar test, stir that dose vigorously for 60 seconds, then gently for 5 minutes, and let sit 30–60 minutes. If floc doesn’t form, repeat with a slightly higher dose; if the water tastes sharp/metallic later, you overdosed—cut back. Alum works best near pH 6–7.5; if your source is acidic (boggy, tea‑colored), a pinch of baking soda can help. Alternatives: chitosan-based floc packs (follow the label) or crushed Moringa seeds (roughly one seed per 1–2 liters, ground and whisked in). Note: floc won’t remove color from tannins; that’s a job for carbon, but pretreating still prevents clogging.

Key takeaway: screen first, settle second, floc if needed. Your goal is clear to weak-tea clarity with a clean surface—ideal feedwater to protect the charcoal bed we’ll build next.

Layered to Perform: Assembling the Two Buckets, Media Depths, Spigots, and Flow Control for Effective Contact Time

Layered to Perform: Assembling the Two Buckets, Media Depths, Spigots, and Flow Control for Effective Contact Time

A backyard creek has turned to chocolate milk and the tap’s gone silent. You’ve got two food-grade 5-gallon (19 L) buckets, bulkhead spigots, and a sack of activated carbon. This is where smart assembly pays dividends: the way you stack media, place spigots, and control flow dictates whether your filter “polishes” floodwater or simply strains it.

Bucket Layout and Spigots

Designate the lower bucket as the filter and the upper as the feed reservoir. Install a food-grade spigot on the filter bucket 1.5–2 inches (4–5 cm) above the bottom to leave a small sump that keeps sediment from the valve. Use a 1/2-inch bulkhead or hose barb with washers inside and out; snug tight by hand plus a quarter turn, and PTFE tape on threads. Leak test with clean water first.

On the upper bucket, install a small ball-valve spigot 1–2 inches (3–5 cm) above the bottom, then run 3/8–1/2 inch silicone tubing down through the filter bucket lid to a diffuser (a perforated plate or cut plastic lid with 2–3 mm holes). This spreads flow so you don’t carve channels in the media. Vent the upper lid with a 1/8-inch (3 mm) hole to prevent “glugging” that spikes flow.

Media Stack and Depths (Bottom to Top)

- Support layer: 0.75–1 inch (2–2.5 cm) of washed pea gravel to protect the spigot area and promote drainage.

- Sand bed: 3–4 inches (7.5–10 cm) of well-rinsed, clean, sharp sand (0.3–1 mm) for fine particulate removal and even flow distribution.

- Activated carbon (GAC): 5–6 inches (12–15 cm). In a standard bucket (30 cm internal diameter), that’s roughly 8–11 liters of GAC—your main adsorption engine.

- Top guard: a tight-weave cloth or felt pad plus the diffuser to prevent scouring.

Wet and tamp each layer to settle voids. Line the bucket wall with a strip of fine mesh or geotextile to discourage bypass along the sides.

Flow Control and Contact Time

Aim for an empty bed contact time (EBCT) of 10–20 minutes for the carbon. Practical setting: 0.25–0.5 L/min through a 8–11 L GAC bed. Use a measuring cup: if it takes ~2–4 minutes to collect 1 liter from the lower spigot, you’re in range. Slower is safer for adsorption; speed only risks breakthrough.

Troubleshooting and Common Mistakes

- Gray or black water: you didn’t rinse GAC/sand enough; recirculate until clear.

- Channeling (quick clear streams): add or improve diffuser, re-level bucket, slow the valve, gently repack the top.

- Leaks at spigots: re-seat gaskets, add PTFE tape, avoid overtightening that warps washers.

- Cross-contamination: keep the clean spigot and hose ends off the ground; dedicate separate lids and rags for “dirty” and “clean.”

Key takeaway: even media, tight seals, and a deliberate flow rate create the contact time carbon needs to work. With the stack built and the flow tuned, we’ll move on to priming, first-run flushing, and performance checks before final disinfection.

Filtering Isn’t Purifying: Post-Filtration Disinfection (Boiling, Chlorine, UV/SODIS) with Field-Proven Dosages

Filtering Isn’t Purifying: Post-Filtration Disinfection (Boiling, Chlorine, UV/SODIS) with Field-Proven Dosages

You’ve run flood runoff through the two-bucket charcoal filter and the water looks crystal. Good—but not done. Filtration strips turbidity and a lot of protozoa and bacteria, but viruses and the smallest pathogens cruise right through. In post-flood water, think norovirus, rotavirus, and leptospira—organisms that require true disinfection. Here’s how to finish the job, with practical doses and timelines that work in the field.

Boiling: The Gold Standard When Fuel Allows

- How: Bring filtered water to a hard rolling boil for 1 minute (3 minutes above 2,000 m/6,500 ft). Let it cool covered.

- Why: Heat inactivates viruses and bacteria reliably regardless of water chemistry.

- Fuel-saver tip: A water pasteurization indicator (WAPI) that flips at ~65°C/149°F proves you’ve hit the temperature that kills pathogens, saving fuel versus a full boil. If you don’t have a WAPI or you’re unsure, default to the rolling boil.

- Common mistakes: Simmering instead of a rolling boil; uncovered cooling (recontamination); pouring back into a dirty container.

Chlorine: Fast, Scalable, Measurable

- Household bleach (unscented, no additives):

- 6% sodium hypochlorite: 8 drops per gallon (≈2 drops per liter).

- 8.25% sodium hypochlorite: 6 drops per gallon (≈1.5 drops per liter; round to 2 drops/L if needed—expect stronger taste).

- Stir, wait 30 minutes. There should be a slight chlorine smell. If not, repeat the dose and wait 15 minutes more. In very cold water (<10°C/50°F) or if the water is still slightly cloudy, double the dose or extend contact time to 60 minutes.

- Pool shock (calcium hypochlorite 65–73%): Make a 1% chlorine stock solution by dissolving 7 g (about a level teaspoon) of HTH in 500 mL of water. Dose at 2.5 mL of this 1% solution per 10 L of water (≈0.5 tsp per 10 L), mix, and wait 30 minutes.

- Why: Aim for ~0.2–0.5 mg/L free chlorine residual after 30 minutes; this correlates with effective virus kill. If you carry test strips, verify residual and redose if needed.

- Taste/odor fixes: Aerate by pouring between containers or neutralize with a pinch of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Note: neutralizing removes protective residual—drink right away.

- Common mistakes: Using scented/“splashless” bleach; not accounting for bleach age (old bleach weakens—use more or switch to HTH); skipping the 30-minute contact time; recontaminating water by dipping an unclean cup.

UV and SODIS: When Fuel Is Scarce and Sun Is Free

- UV pens: Treat clear water only. Follow the device volume/time (e.g., 1 L for ~90 seconds), stirring to avoid shadow zones. Carry spare batteries.

- SODIS (solar disinfection): Fill clear PET bottles (≤2 L), shake to oxygenate, lay them horizontally on reflective metal or dark roofing. Full sun: 6 hours. Overcast: 2 consecutive days. Ensure water clarity (you should be able to read newsprint through the bottle); if not, re-filter.

- Why: UV-A plus heat inactivates most viruses and bacteria when turbidity is low and exposure time is sufficient.

- Common mistakes: Using colored/cloudy bottles; stacking bottles; partial sun exposure; bringing bottles in too soon; using glass (blocks more UV-A).

Key takeaways: Filtering makes water look safe; disinfection makes it drinkable. Pick the method that matches your constraints—boil when you can, chlorinate when you need speed and volume, and use UV/SODIS when fuel is tight and the sun is out. Next, we’ll lock in safety with clean storage and recontamination prevention.

Field Hardening the System: Maintenance Schedules, Media Regeneration/Replacement, Testing, and Troubleshooting

Day four after the flood, your filter is still producing, but the flow has sagged and there’s a faint marshy tang in the cup. This is where systems fail or mature. Field hardening isn’t glamorous, but it’s what turns a clever build into reliable daily water.

Maintenance Rhythm: Daily, Weekly, After-Event

- Daily: Log source (ditch, rooftop), pretreatment used, and output flow. Time a 1-liter fill at the spigot; your baseline is whatever you recorded after the first 24 hours of stabilized operation. A drop of >30% signals intervention. Wipe lids and spigots with 1% bleach solution (20 mL household bleach per 2 L water) to keep biofilm off contact surfaces.

- Weekly (or every ~100–150 L processed in dirty flood conditions): Stir-and-skim the top 1–2 cm of the sand/fine layer to lift trapped silt; replace that skimmed portion with prewashed sand. Inspect gaskets, bulkhead fittings, and hoses for drips or salt crust; snug with a quarter-turn, not a full crank.

- After heavy turbidity events: Drain, remove top media layer, and rinse until the wash water runs clear. Expect to discard 5–10% of your fine media each time.

Why: Flow is your canary. Decline comes from clogging (fine silt), channeling (uneven surfaces), or air locks. Regular light maintenance preserves adsorption capacity and prevents bypass.

Media Care: What to Regenerate, What to Replace

- Activated charcoal: In field use, you can rinse and sun-dry to drive off volatiles, but you cannot truly “reactivate” it without industrial heat. Plan to replace the carbon layer every 100–150 L of nasty water or any time fuel/chemical odors break through. Carry 1–2 kg spare. If you must make emergency hardwood charcoal, crush to pea-to-rice size, rinse until grey water runs clear, and swap in.

- Sand/fines: Keep them. Rinse and reuse; only the top crust needs regular refresh. Gravel/rinse layers are effectively permanent.

Testing and Verification: Trust, but Verify

- Clarity: Do a jar test. If you can’t read 12-point text through a 5 cm column, extend settling and cloth prefiltering.

- Flow: Record liters per minute. Drops >30% = service. Sudden increases = channeling; relevel media.

- Disinfection: Post-filter disinfection is non-negotiable. Use chlorine test strips to confirm 0.2–0.5 mg/L free chlorine after 30 minutes contact, or boil for one minute (three at altitude). Remember: carbon will strip chlorine; disinfect after filtering, not before.

- Quick screens: Food-coloring dye in the upper bucket should never show in the lower bucket during an empty-chamber check—if it does, you have a bypass. TDS pens don’t measure safety; they only show dissolved ions, not pathogens.

Troubleshooting: Fast Fixes to Common Failures

- Sluggish flow: Increase pretreatment (double the settling time, add a tight-knit cloth layer), skim and replace top fines, burp the spigot to clear air.

- Cloudy output: New media wasn’t rinsed enough; run 2–3 L to waste. Check for channeling; gently tamp and relevel.

- Off-odors: Immediate carbon replacement. If gasoline or pesticide smell persists after a fresh carbon swap, reject that source—charcoal has limits.

- Leaks and bypass: Tighten bulkheads; add a food-grade gasket. Hairline bucket cracks? Heat-weld with a soldering iron and back with epoxy patch, then re-test with dyed water.

- Algae in clear buckets: Opaque wrap or paint; sunlight feeds growth in warm climates. Cold snaps: Drain overnight to prevent freeze cracks.

Key takeaway: Treat the filter like a tool with a schedule. Log flow, protect the disinfection step, replace carbon on breakthrough, and attack clogs at the top layer before they become system failures. Reliable water is maintenance made visible.

When the ditches turn to chocolate milk and taps go dead, this two-bucket charcoal filter gives you control: clarify the chaos, then finish the job with disinfection. The essentials are simple but non‑negotiable. Start with pretreatment—let muddy runoff settle 12–24 hours, decant carefully, and screen through cloth; if turbidity stays stubborn, dose a pinch of alum (about 1/8 tsp per gallon), stir 5 minutes, and give it 30–60 minutes to floc and fall. Build with food‑grade buckets, tight bulkhead fittings, and clean media: a gravel underdrain, 2–3 inches of fine sand, and 8–10 inches of rinsed GAC. Meter flow to a slow drip—around 0.5 L/min—to hit at least 10 minutes of contact time and avoid channeling. Remember the limit: filtration polishes, it doesn’t sterilize. Finish with heat or a measured dose of chlorine and verify a small free chlorine residual after 30 minutes.

Your next moves are straightforward. Assemble the kit now, pre‑drill and leak‑test, and run a muddy practice batch end‑to‑end. Stock spares: extra GAC, gaskets, a spare spigot, alum, a WAPI or thermometer, unscented bleach (dated and rotated), a 1 mL dropper, and chlorine test strips. Print a one‑page SOP with your flow rate, alum dose, and disinfection targets, and tape it inside the lid. Keep a log: liters filtered, media changes, taste/odor notes.

With a little bench time today, you won’t be guessing when the water goes brown—you’ll be pouring clear, safe cups on demand. Build it. Practice it. Own your water.