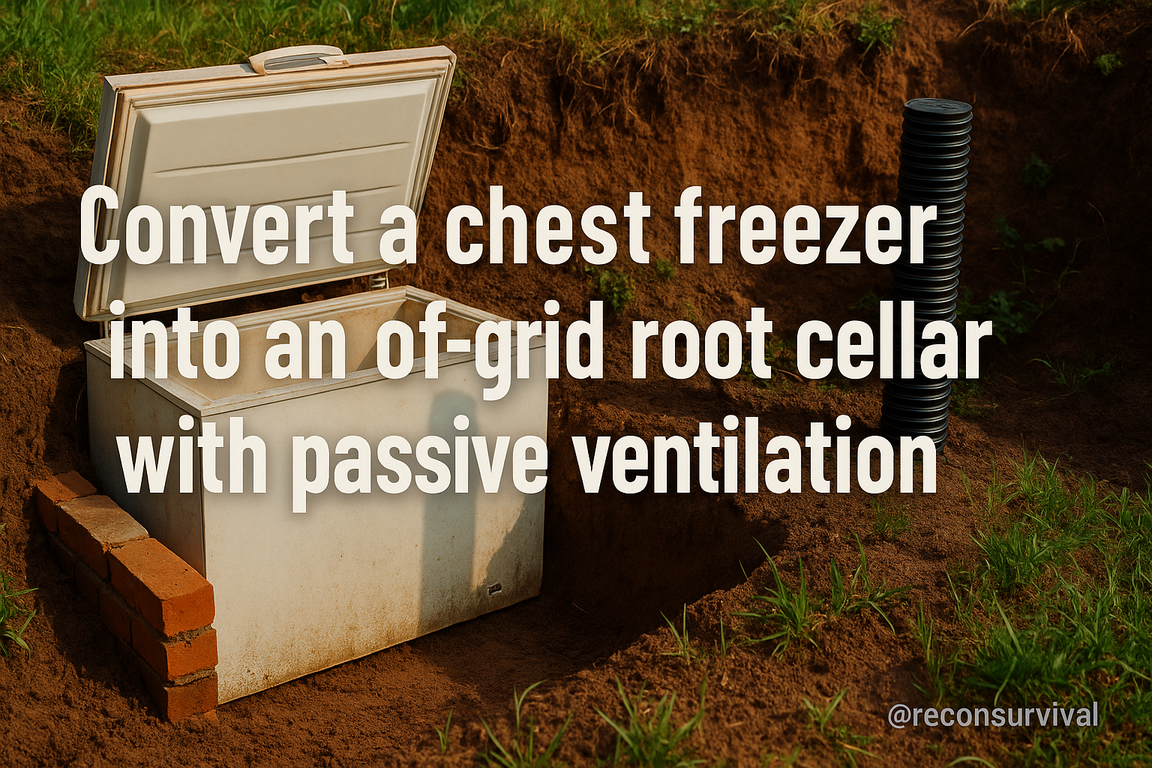

Last fall, a windstorm knocked out power across our county for four days. Generators hummed, coolers filled with melting ice, and neighbors watched garden bounty go soft. Meanwhile, an old chest freezer buried behind my shed quietly held 200+ pounds of potatoes, carrots, beets, and apples at 35–40°F without a single watt. Here’s the thing: the U.S. throws away roughly a third of its food supply, much of it produce. A simple, off-grid root cellar made from a retired chest freezer can turn waste into winter security—and it’s faster and cheaper than pouring a concrete vault.

I’ve built and tuned these “freezer cellars” in clay, sand, and rocky soils, for my own family and for church friends who wanted to steward their harvest well and share with others when the lights go out. Done right, you’ll hit stable temps, 90–95% humidity for root crops, and rodent-proof storage that lasts through spring. Done wrong, you’ll fight condensation, mold, and freeze-ups.

This guide is a step-by-step blueprint seasoned by field experience: choosing the right freezer and site, safe decommissioning, digging and drainage that won’t flood in a November rain, and passive ventilation that actually breathes—sizing intake and exhaust, routing to prevent cold sinks, and using simple baffles to balance humidity. We’ll dial in temperature targets by crop, manage condensation without electricity, and cover lids, gaskets, and baskets that make access easy in January. You’ll see real dimensions, airflow calculations you can do with a pencil, and the mistakes I made so you don’t repeat them.

If you want resilient food storage that honors the work you’ve put into your harvest—and leaves you with enough to bless your neighbors—let’s convert that “dead” freezer into an asset. It’s a weekend project with year-round dividends.

Selecting and retiring a chest freezer for cellar duty: safe decommissioning, size, and materials

You find a free, nonworking chest freezer on a neighbor’s curb the week your garden explodes with potatoes and beets. Perfect timing—if it’s the right box. Before you turn any old appliance into a year-round pantry, choose wisely and retire it safely. Good stewardship means picking materials that will last underground and decommissioning without creating hazards.

What to look for: size, shape, and liner

- Capacity and layout: For most families, a 10–15 cu ft chest balances storage and manageable weight. Internal dimensions in this range typically run about 36–48 in long, 18–22 in front-to-back, and 16–20 in depth—enough for two rows of 18 x 12 x 9 in harvest crates with airflow gaps. A compact 7–9 cu ft unit fits 4–6 five-gallon buckets; a 14–20 cu ft unit can handle 8–12 buckets or mixed crates.

- Liner material: Favor smooth aluminum or powder‑coated steel liners over brittle plastics. Metal liners resist abrasion, clean easily, and tolerate high humidity. Avoid units with cracked liners—moisture will infiltrate the foam and breed mold.

- Insulation and shell: Most modern chest freezers use polyurethane foam with decent R-value. Inspect for rust-through on corners and the bottom edge; surface rust is fine, but structural rot is not. A sound lid and intact gasket matter—you’ll need that seal to control humidity while passive vents handle air exchange.

- Drain port: A bottom drain is a plus for cleaning and optional condensate management. Confirm the plug is present, or plan to replace it with a rubber stopper later.

Safe decommissioning: do it by the book

- Refrigerant recovery: Whether it’s R134a or flammable R600a (isobutane), don’t cut lines or “vent it.” Call a certified tech or appliance recycler to evacuate refrigerant and compressor oil; get a receipt. It’s both safer and often free.

- Component removal: After recovery, a simple tubing cutter lets you detach the compressor and condenser coil. Unbolt, lift off, and tape over any open stubs. This reduces weight, eliminates rust-prone parts, and makes burial cleaner.

- Cleaning: Defrost, then scrub the interior with hot water and baking soda (1/4 cup per gallon). Stubborn odors respond to 3% hydrogen peroxide wipes. Rinse and dry thoroughly.

Common mistakes and troubleshooting

- Leaving a locking latch intact creates entrapment risk. Remove or disable it now; keep the hinges.

- Buying units with hidden foam saturation: press on suspect areas—spongy spots or “sour” smells suggest waterlogged insulation.

- Overestimating usable volume: plan on 60–70% of rated capacity after crates, airflow, and vent hardware.

Key takeaway: choose a structurally sound, mid-size metal‑lined chest; decommission refrigerant professionally; and keep the lid seal. Next, we’ll select a site and plan burial depth and passive ventilation so your “freezer cellar” holds steady temps without power.

Siting and burying the freezer: drainage, frost depth, and insulation for stable ground temps

Siting and burying the freezer: drainage, frost depth, and insulation for stable ground temps

A September downpour will test your build before your carrots do. Picture rain pooling around a poorly placed pit—silt washes in, the freezer floats an inch, and your “root cellar” becomes a bathtub. Smart siting and burial make the difference between steady 38–50°F storage and a damp headache.

Choose high, well-drained ground

- Elevation and slope: Favor a knoll or the high side of your yard with 2–5% natural fall. Avoid swales and downspouts. Keep at least 10 ft from large trees (roots) and 15 ft from septic components. Check utilities before digging (811 in the U.S.).

- Sun and access: North or east side of a building stays cooler; ensure wheelbarrow access and room to service ventilation.

Why: Gravity is your friend. Water that never arrives never needs pumping. Good stewardship also means not redirecting runoff onto a neighbor—shape your site with community in mind.

Build a “dry crib” around the freezer

- Excavation: Dig a pit 12–18 in wider and 8–12 in longer than the freezer. Depth depends on climate (see frost, below).

- Base: Lay 6 in of 3/4-in washed stone, compacted, topped with a level 1–2 in sand bed to protect the freezer’s underside.

- Perimeter drain: Set a loop of 4-in perforated drain pipe at the base, sloped 1% (1/8 in per foot) to daylight or a dry well. Wrap pipe and stone in nonwoven geotextile to keep fines out.

Why: The gravel bed relieves hydrostatic pressure and lets any seepage leave. The geotextile keeps your system from silting up in the first season.

Respect frost depth—and cheat it smartly

- Cold climates (frost >24 in): Aim for the top of the freezer at or below frost depth if feasible. Where that’s impractical, use frost-protected shallow foundation methods: 2–4 in XPS/EPS insulation across the lid and down the sides, plus a horizontal “wing” of 2 in foam extending 24–48 in out from the lid edge, buried 12 in deep. Berm with 12–18 in of soil.

- Moderate/warm climates (frost ≤12 in): Bury to just below grade with 2 in foam lid insulation and a 24-in foam wing.

Why: Stable ground temps live below seasonal swings. If you can’t reach that depth, you expand the “thermal mass” with foam and soil to blunt winter cold and summer heat.

Insulation details that last

- Materials: Use 25 psi (Type IX EPS or XPS) rigid foam. Tape seams; protect foam with 6-mil poly above, then 3/4-in treated plywood. Cap soil with a pond liner or EPDM as a shed roof under mulch.

- Pests: Add metal flashing/termite shield at the lid perimeter; hardware cloth on any penetrations.

Troubleshooting and common mistakes

- Mistake: Burying in a low spot. Symptom: Water in the pit after rain. Fix: Add a daylight drain or relocate; French drains rarely overcome a bad site.

- Mistake: No slope on drain tile. Symptom: Standing water in pipe. Fix: Regrade to 1% minimum or install a dry well lower than the pit base.

- Mistake: Minimal foam in cold zones. Symptom: Produce freezing near lid. Fix: Add lid foam and extend the horizontal wing.

- Mistake: Soil in direct contact with painted steel. Symptom: Rust at corners. Fix: Use rubberized/asphalt coating on freezer exterior or line pit walls with dimpled drain mat before backfill.

Key takeaways: pick high ground, give water an exit, and use insulation to create a stable thermal envelope, especially where frost is deep. Next, we’ll tie this stable shell to passive ventilation so temperature and humidity stay in the sweet spot without grid power.

Designing passive ventilation: intake/exhaust placement, pipe sizing, and condensation control

Designing passive ventilation: intake/exhaust placement, pipe sizing, and condensation control

A friend converted a 10 cu ft chest freezer and was frustrated that it kept swinging from too warm to too wet. The fix wasn’t exotic—just proper passive ventilation. In a root cellar, air movement is a tool, not a torrent. Set the system to move slowly and predictably, and your harvest will keep like it was meant to. As good stewards, we design it once, and let gravity and temperature do the work.

Stack effect and placement

- Intake low, exhaust high: Drill the intake near the bottom sidewall and the exhaust through the lid or top corner. Cool air sinks to the lowest point; warm, ethylene-laden air rises. Give it a path.

- Height difference drives flow: Aim for at least 24–48 inches of vertical separation between intake and exhaust caps. If the freezer sits in a shed, run the exhaust pipe up an exterior wall to gain height. A sun-warmed (painted black) exhaust stack can add a gentle “solar chimney” boost on mild days.

- Orientation: Pull intake air from shaded, north-side air when possible. Keep both vents away from compost piles or fuel vapors.

Pipe sizing made simple

- For 5–12 cu ft units, a 2-inch intake and 3-inch exhaust balance flow and resistance. Cross-sectional areas: 2 in = ~3.1 in²; 3 in = ~7.1 in², giving a slight bias to exhaust.

- Larger boxes (15–20 cu ft): bump to 3-inch intake and 3–4-inch exhaust.

- Keep runs short and smooth. Each 90° elbow “adds” several feet of effective length. Use long-radius elbows when you can.

- Add control: Install a simple in-line damper or sliding cap on both vents to throttle airflow seasonally. Half-closed in deep winter, more open in shoulder seasons.

Moisture and condensation control

- Humidity is good for produce (90–95%), puddles are not. Slope the intake pipe slightly outward (about 1/4 inch per foot) so condensation drains outside.

- Add a drip leg: On the exhaust, use a tee with a short vertical “leg” ending in a removable cap; empty it weekly during shoulder seasons.

- Insulate exposed vent pipes with 1-inch foam wrap to reduce interior sweating. Cap vents with rain hoods; back them up with fine insect screen (1/16-inch) and 1/4-inch hardware cloth for rodents.

Troubleshooting and common mistakes

- Too warm/stale: Increase stack height, open dampers, or upsize exhaust. Ensure intake isn’t blocked by a basket or wall.

- Too cold/dry: Partially close dampers, reduce stack height (temporary sleeve), or insulate the exhaust stack.

- Condensation pooling inside: Add the drip leg and slope; elevate produce on a slatted rack above a gravel tray.

- Forgetting screens: Mice love tight spaces—screen both ends, twice.

Key takeaway: Design for a gentle, controllable stack effect—low intake, high exhaust, balanced pipe sizes, and a plan for water. With vents sorted, we can cut and seal the penetrations cleanly and move on to dialing in temperature and humidity control.

Converting the box: sealing penetrations, lid modifications, shelving, and pest-proofing

Picture the freezer carcass sitting in the shade, compressor removed, foam core intact. This is where stewardship meets craftsmanship: turning a castoff into a season-saving tool that serves your household and neighbors. The key now is to treat it like a small building—tight where it must be tight, breathable where it must be breathable.

Seal penetrations and restore the vapor barrier

- Identify holes: After de-gutting, you’ll usually have line-set holes on the back or bottom and a factory drain. Dry everything thoroughly.

- Small holes (<1″): Pack with copper mesh (it deters gnawing), then inject minimal-expanding closed-cell spray foam. Once cured, trim flush and overcoat with polyurethane sealant or butyl tape, then foil HVAC tape. Why: foam insulates, butyl/foil restores the vapor barrier so moist air can’t soak the insulation.

- Large holes (≥1″): Sandwich the area with 26–30 gauge galvanized patches inside and out, bedded in exterior-grade silicone, secured with pop rivets or #8 x 3/4″ stainless screws. Seal edges with butyl and foil tape.

- Drain management: If you keep the drain, install a 3/4″ bulkhead fitting and a short barbed elbow to a gravel sump outside the box. A slight shim (plastic cutting board slice) can create 1–2% slope for condensate. Why: controlled drainage prevents puddling and mold without inviting pests.

Troubleshooting: If you see condensation on interior walls, your vapor barrier is compromised. Smoke-test with an incense stick around seams; leaks will draw smoke.

Upgrade the lid for airtight, serviceable access

- Gasket: Peel the old one and install 1/2″ EPDM D-profile weatherstripping. Clean mating surfaces with isopropyl alcohol first. Add two adjustable draw latches to ensure even compression.

- Insulation: Laminate 1–2″ polyiso board (R-6 to R-12) under the lid using construction adhesive and foil tape the seams. Leave clearance around vent penetrations.

- Hardware: Add a gas strut or prop rod so the lid can stay open safely in cold weather. Consider a padlock hasp if you’ve had raccoon “inspections.”

Common mistake: Over-stuffing the lid insulation and blocking the gasket from fully seating. Check for uniform contact with a strip of paper; it should “drag” all the way around.

Build breathable, strong shelving

- Materials: 1×2 or 2×2 cedar frame with slatted tops (1″ gaps) or food-safe wire shelving. Keep shelves 1–2″ off the walls for airflow.

- Layout: Two tiers work well—lower shelf 8–10″ high for roots; upper 10–12″ for squash or crates. Design for 50–100 lb per shelf; use stainless screws for longevity.

- Containers: Ventilated totes or perforated crates. Segregate strong ethylene producers (apples) from potatoes and squash.

Tip: Mark shelf zones for “high humidity” and “drier” based on proximity to vent paths; it helps maintain consistent quality.

Pest-proof like a barn, not a pantry

- Vents: Double-screen with 1/4″ stainless hardware cloth inside and out; secure with stainless hose clamps to the vent tubes.

- Edges: Any exposed foam gets capped with aluminum flashing or plastic U-channel. Rodents chew foam; they avoid metal.

- Perimeter: Maintain an 18″ vegetation-free gravel skirt around the installation. Set snap traps in covered boxes outside the cellar, not inside with produce.

Key takeaways: Seal every unintended hole to protect insulation and moisture control; upgrade the lid for reliable compression; build shelves that breathe and bear weight; and harden every edge against pests. With the box converted, you’re ready to integrate the passive vent stack and start tuning airflow in the next step.

Managing humidity and produce: target ranges, storage media, and mold prevention

You open the lid after the first hard frost: the air is cool and earthy, but your carrots feel rubbery and the onions show fuzzy spots. In a chest-freezer root cellar, humidity is the difference between crisp and compost. Manage it on purpose, and your harvest will carry you—and maybe a neighbor—through the lean months. That’s faithful stewardship in practice.

Know Your Targets

- High-humidity crops (90–95% RH, 32–40°F): carrots, beets, parsnips, potatoes, cabbage, rutabagas, leeks. Why: they’re mostly water; high RH slows dehydration and preserves texture.

- Moderate humidity (80–90% RH, 32–40°F): apples, pears. Note: high humidity is good, but apples off-gas ethylene—keep them away from roots.

- Low humidity (60–70% RH, 32–50°F): onions, garlic, winter squash (warmer end for squash). Why: drier air prevents neck rot and mold on cured skins.

Place a reliable hygrometer at mid-height; calibrate it with a salt test: a bottle cap of damp table salt sealed in a zipper bag with the hygrometer for 8+ hours should read 75% RH; note any offset.

Storage Media and Containers

- Damp media for roots: Layer carrots or beets in food-grade totes with 1–2 inches of damp sand, sawdust, or vermiculite between layers. Aim for media that clumps lightly but doesn’t drip. This creates a microclimate at 95% RH around the produce.

- Ventilated containers: Use slatted wooden crates or perforated totes for potatoes and cabbage. For onions/garlic, use mesh bags or open crates—no damp media.

- Humidity buffers: If RH is low, add a shallow tray (9×13 inch) of water or hang a damp burlap strip; if too high, set out a tray of rock salt or calcium chloride, and increase passive airflow during the coolest part of evening.

- Separation: Store apples high and near the exhaust vent; roots low and toward intake. Ethylene from apples accelerates sprouting/bitterness in roots—“one bad apple” is literal here.

Mold Prevention and Troubleshooting

- Cure before storing: Potatoes (50–60°F, 85–95% RH, 10–14 days), onions/garlic (warm, dry airflow 2–3 weeks until necks seal), winter squash (80–85°F, 10 days). Curing toughens skins and reduces rot.

- Sanitize seasonally: Wipe interior with 1 tablespoon unscented bleach per gallon of water; dry before loading.

- Watch for condensation under the lid—sign of warm, moist air. Improve insulation on the lid and crack the exhaust slightly overnight.

- Symptoms and fixes:

- Rubberiness/shriveling: RH too low—add damp media or water tray.

- Slimy carrots: media too wet—mix in dry sand, increase airflow.

- Onion mold: humidity too high or poor cure—move to drier zone.

- Sprouting potatoes: ethylene exposure or temps too warm—separate from apples; maintain 38–40°F.

Key takeaway: match the crop to its humidity zone, use the right media, and adjust RH with simple buffers. Next, we’ll tie it all together with a maintenance routine and seasonal adjustments to keep your cellar steady through spring.

Operating off-grid through the seasons: monitoring, troubleshooting, and maintenance routines

Operating off-grid through the seasons: monitoring, troubleshooting, and maintenance routines

When the first hard frost hits and your “freezer cellar” is packed with potatoes, carrots, and a few dozen apples from the neighbor’s tree, the real work begins: keeping that microclimate steady without a plug or a compressor. Think of it like tending a woodstove—small, regular adjustments beat big, infrequent interventions.

Monitor what matters: temperature, humidity, and trends

- Targets: Most root crops prefer 34–40°F with 85–95% RH. Potatoes are happiest at 38–40°F; carrots, beets, and parsnips tolerate 32–36°F; onions/garlic want cooler and drier (32–35°F, 60–70% RH) and do best segregated in a lidded tote with a handful of desiccant or rice.

- Tools: Use a min/max thermometer-hygrometer with a remote probe (AA battery models run a year). Place the probe mid-height, center mass of stored food, not near the lid or vents.

- Frequency: Check daily the first week after loading, then 2–3x weekly. Log highs/lows and outside weather. Trends tell you what to tweak.

- Calibration: Every season, verify hygrometers with a salt test—fill a bottle cap with table salt, add a few drops of water to make a slushy paste, seal with the sensor in a zipper bag or jar for 8–12 hours. It should read ~75% RH. Note any offset.

Why: Stable cold slows respiration and rot; high humidity prevents wilting. Tracking trends lets you adjust vents and thermal mass before spoilage starts.

Seasonal adjustments: small dials, big results

- Winter (sub-freezing): Prevent freezing. If the interior hits 33°F for hours, close the intake to a sliver (10–20%) and leave the exhaust cracked for minimal airflow. Add thermal mass: 4–8 one-gallon water jugs (8.3 lb each) buffer cold snaps. Lay a breathable blanket over bins and add straw around containers for insulation. A cheap low-temp alarm (set at 33°F) can save a harvest.

- Shoulder seasons: Expect swings. Open both vents fully on cool nights to purge heat; throttle to half during warm days. Keep produce off the metal floor with slats so any condensation drains and surfaces can dry.

- Summer heat: Your goal is nocturnal cooling. Open vents at night; close or restrict the intake during hot days. Shade the lid with a reflective cover. If you have a cool well or spring, swap in pre-chilled jugs weekly to add “coolth.” Apples and squash emit ethylene—store away from potatoes and roots to avoid sprouting and off flavors.

Why: Passive systems rely on diurnal temperature differences and thermal mass. Night venting removes stored heat; daytime restriction limits warm, humid infiltration.

Troubleshooting and routine care

- Condensation and moldy smell: Usually from warm daytime intake. Solution: tighten daytime intake damper, increase night purge, elevate bins, and wipe surfaces with 1:1 white vinegar/water (or 1 Tbsp unscented bleach per gallon of water). Dry thoroughly. Add a shallow tray of biochar or baking soda to absorb odors.

- Wilting produce: RH too low. Mist the floor lightly, add a damp towel over crates (not touching produce), or set a shallow pan of water near the intake. Don’t overdo it—aim for 90% RH, not dripping walls.

- Sprouting potatoes or bitter taste: Too warm or exposed to ethylene. Drop to 38–40°F, block light leaks, and move apples/squash elsewhere.

- Frosted carrots or cracked jars: Too cold, too fast. Add more water jugs, throttle vents, and add a lid liner (thin closed-cell foam) to slow heat loss.

- Pests: Inspect screens monthly; use 1/8″ hardware cloth on vent ends. Sweep crumbs, remove culls promptly. One bad apple can condemn a bin—cull weekly.

Maintenance rhythm:

– Monthly: Check gaskets, hinges, and caulk seams; wipe down interior; verify vent dampers move freely; inspect for rust under bins.

– Quarterly: Calibrate instruments, rinse/replace desiccants, clean or replace bug screens, re-level the unit so door seals evenly.

– After each season: Deep clean, air-dry with vents open for 24 hours, then close to keep critters out.

Key takeaways: Off-grid operation is stewardship by rhythm—observe, record, adjust. Small, consistent care through the seasons preserves food, saves labor, and lets you bless others with the surplus. Your cellar doesn’t have to be perfect; it has to be predictable. Keep the logbook, mind the vents, and the harvest will keep you.

Picture the first hard frost: you lift the insulated lid and a breath of clean, cold earth rolls out. The “dead” freezer is now a quiet partner—steady temps from good siting and drainage, calm airflow from correctly placed vents, and produce resting in the right humidity instead of sweating or shriveling. That’s the payoff for doing the right things in the right order—retire the unit safely, bury it above the water table on a gravel bed, size and slope your intake and exhaust to manage condensation, seal the box like a drum, and then run it with a light but steady hand through the seasons.

Actionable next steps:

– Walk your property after a rain to spot high, well-drained ground. Pull local frost-depth data and call 811 before digging.

– Sketch your layout: lid orientation, 4–6 inch intake low and away from the sun, exhaust high and short, both screened and sloped for drip.

– Gather materials: coarse gravel, landscape fabric, rigid foam, silicone and butyl, EPDM gasket, hardware cloth, a hygrometer/thermometer, and food-safe bins, sand/sawdust, or perforated bags for crop storage.

– Block two weekends: set the box and drainage first; venting, sealing, and shelving second. Test a week with water jugs and sensors before you trust your harvest.

Common mistakes—shallow placement, flat vents, unsealed penetrations, and over-dry conditions—are easy to avoid if you plan and measure twice. Build it, share the work with a neighbor, and teach a kid to read the gauges. Turning waste into provision is wise stewardship, and a gift to your household and community. Do the quiet, faithful work now and let that hidden cellar buy you margin all winter long.