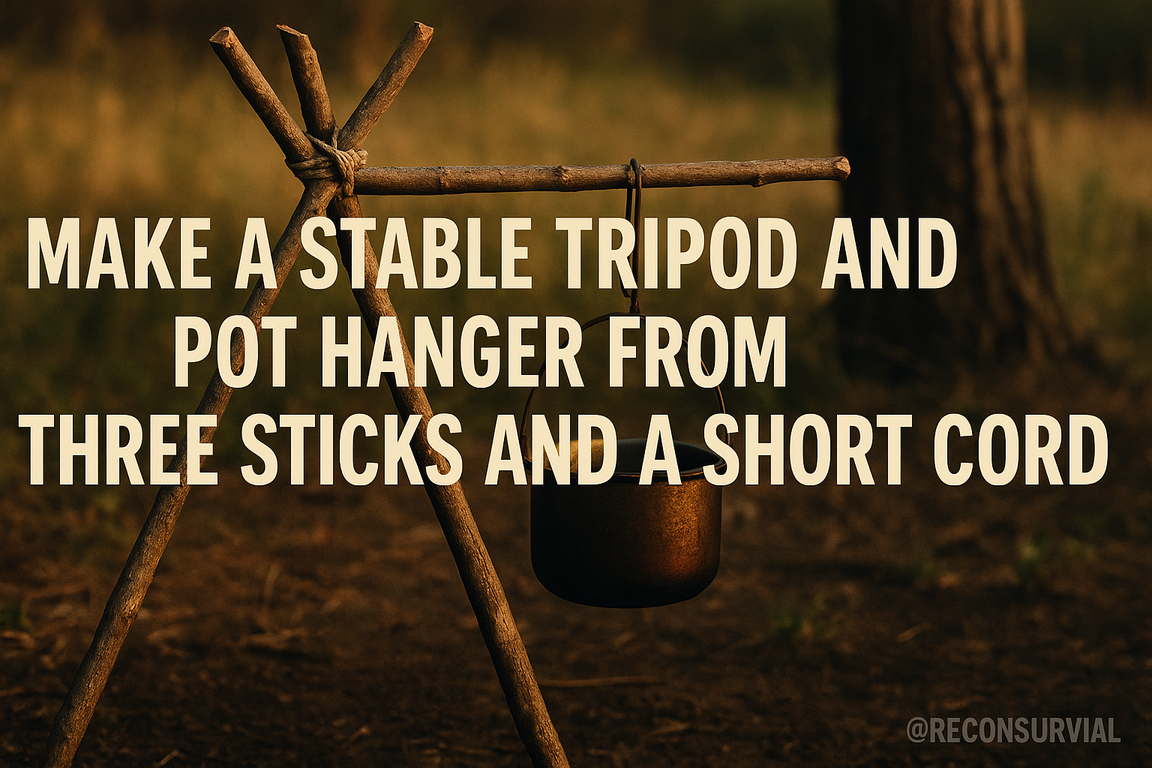

Wind knifes across the ridge and the last of the blue light drains from the sky. Your stove sputters, the pot rocks, and a half-gallon of dinner threatens to swan-dive into the coals. A spilled meal isn’t just demoralizing—it wastes fuel, invites burns, and robs you of heat when you need it most. A stable cook station is not a luxury in the field; it’s a force multiplier. With three sticks and a short cord, you can build one in minutes—strong, adjustable, and safe enough to swing a Dutch oven over a hard boil.

I’ve taught this setup to wildland firefighters, cold-weather students, and SAR teams who can’t afford “good enough.” Done right, a tripod and pot hanger will hold steady in gusts, shed bumps and snags, and give you clean height control for simmer, boil, and bake. Done sloppy, it collapses when the stew is finally ready. The difference is a handful of details and an understanding of why they matter.

In this guide we’ll pick the right sticks (length, diameter, and species that won’t shear under load), site the tripod so wind and slope work for you, and tie a compact lashing that uses surprisingly little cord but locks solid—no mystery knots, just deliberate wraps and friction. You’ll learn the quick, glove-friendly hanger with a toggle that won’t twist the pot bail, plus fast adjustments that don’t dump supper. We’ll cover leg splay angles that carry weight efficiently, how to prevent skating on frozen ground, and what to do when all you have is slick nylon line. Expect real dimensions, failure points, and fixes.

If your cooking setup has ever felt like a game of Jenga over fire, read on. This is how you make it bombproof with almost nothing.

Pick the Right Wood and Ground: Dimensions, Deadfall Selection, and Site Safety for a Rock-Solid Tripod

You’ve got stew in mind, daylight fading, and a cold breeze that says “cook now or eat cold.” You drag three random sticks together, throw a cord around the tops, and—wobble. The pot swings, two legs skitter, and the whole thing wants to fold into the fire. The fix starts long before the knot: pick the right wood and ground, and a stable tripod almost builds itself.

Dimensions That Work

For most camp cooking (2–4 liters/2–4 quarts), aim for three straight poles 5–6 feet (150–180 cm) long, roughly wrist-thick at the base: 1.25–1.5 inches (3–4 cm) diameter. This gives you enough height to clear flames and enough mass to resist twist. If you’ll hang a cast-iron Dutch oven (5–9 kg/10–20 lb loaded), step up to 6.5–7 feet (200–215 cm) and 2–2.5 inches (5–6.5 cm) diameter. Keep lengths within 1 inch of each other; uneven legs telegraph into a lurchy, off-center apex.

Why these numbers? Stability comes from footprint and mass. A tripod is happiest when its feet form an equilateral triangle with a span about 60–70% of leg length. With 6-foot legs, plan on a footprint about 44–50 inches across. This splay angle resists tipping while keeping your cord and hanger a safe 12–18 inches above flame tips.

Smart Deadfall Selection

Use straight, sound poles with minimal knots near the apex—knots create pressure points that encourage slipping. Dead-standing hardwood (oak, maple, hickory, birch) is ideal: lighter than green but still strong. Thumb test the wood; if your nail dents deeply or the surface powders, it’s punky—pass. You should hear a clean “tock,” not a dull “thud,” when you rap it against another stick.

Green wood works too, and is more resistant to embers charring—alder, willow, and fresh birch are common riverbank wins. Just remember green wood is heavier; size down slightly if needed. Conifers are fine in a pinch, but avoid resin-heavy, cracked, or spiral-grained pieces that twist under load. Bark-on gives friction at the lashing and helps resist leg creep; if you’re using slick birch, score shallow crosshatches near the apex to give the cord something to bite.

Ground Truth: Where You Stand Matters

Set up on compact, mineral soil—scrape away duff down to dirt. Avoid root mats, moss pillows, and ash pits that settle once the tripod is loaded. If the site slopes, place two legs uphill and one downhill; then kick shallow “cups” for the feet so they seat and don’t skate. On sand or snow, widen the base and bed each foot on a flat stone or short cross-stick to prevent sinking. Keep the tripod just outside the flame column—offset it slightly downwind so heat and smoke don’t cook your cord.

Scan overhead for widowmakers, especially when using dead-standing poles. Keep the legs outside the fire ring’s edge by at least a hand’s breadth to reduce ember strikes and ensure the lashing sits high and cool.

Troubleshooting and Common Mistakes

- Wobble after loading: Your legs are too thin or the footprint too narrow. Thicken up or widen to that 60–70% rule.

- Legs sliding on glossy bark: Roughen contact areas or leave bark on and add a shallow notch at the apex.

- Sinking feet: Use stones or cross-sticks; on peat or ash, dig to firm mineral soil.

- One leg pops out during setup: Likely a length mismatch or a knotted bulge at the apex. Trim ends to match and keep the top 8–10 inches relatively smooth.

Key takeaway: choose straight, sound poles sized to your pot, and plant them on firm, clean ground with a deliberate footprint. With wood and site dialed in, the lashing is the easy part. Next, we’ll bind the apex with a short cord so the tripod swings open smoothly and locks solid under load.

Minimal-Cord Tripod Lashing: A Fast, Secure Wrap-and-Frap System That Works with 3–6 Feet of Line

Minimal-Cord Tripod Lashing: A Fast, Secure Wrap-and-Frap System That Works with 3–6 Feet of Line

Picture dusk creeping in, a storm pushing across the ridge, and you’ve got three stout sticks and a few feet of cord left on the spool. You still need a cooking tripod up in minutes. This wrap-and-frap lashing is designed for exactly that moment—fast to tie, stingy on cord, and reliable under a hot, swinging pot.

Why This Works with So Little Line

A tripod lashing isn’t about tying the legs together; it’s about creating friction and controlled compression. The wraps bind the legs as a bundle; the fraps (tight turns cinched between the legs) compress the bundle so the wraps bite into the wood. When you spread the legs, the hinge action increases friction and self-locks under load. Get the wraps tight and the fraps harder—friction does the rest.

Step-by-Step: The Minimal Wrap-and-Frap

- Select and position: Choose three legs about 5–6 ft long and 1.5–2.5 in diameter. Align their top ends even, with the eventual “front” and “back” legs outside and the “hinge” leg between them. Lash 2–3 in below the tips so the ends don’t pop past the lashing.

- Start knot: With 3–6 ft of #36 bank line or 550 paracord, anchor a constrictor or tight clove hitch around one of the outside legs. Constrictor grips better on slick bark and uses little cord. Leave a 2–3 in tail.

- Wrap: Run the working end around all three legs 4–6 tight turns, stacking each wrap neatly beside the last to make a 1–1.5 in wide band. Pull hard on every pass—use your body weight. Keep wraps parallel; crossing wastes cord and loses friction.

- Frap: Pass the line between the first and second legs and pull a hard “tourniquet” turn around the wrap bundle—1–2 turns. Repeat between the second and third legs, then between the third and first. These three frap stations tighten the whole system.

- Finish: Lock with two half hitches or a small constrictor around a leg opposite your start. Dress and set the knot under tension. Spread the legs into a stable triangle; the lashing should hinge but not slip.

Cord budgeting: With roughly 3 ft of line, aim for 4 wraps and 1 frap per gap. With 5–6 ft, do 5–6 wraps and 2 fraps per gap. Bank line grips best; paracord has stretch—pre-stretch it and consider an extra frap.

Troubleshooting the Common Failures

- Lashing slides down: Move the lashing 1–2 in lower, carve shallow 1/8 in stop grooves, or rough the bark with your knife. Add one more wrap. Ensure fraps go around the wraps, not the legs.

- Legs won’t spread smoothly: Wraps too tight or set too low. Re-seat the lashing 2–3 in from the tips and reduce one frap turn.

- Creaking/settling under load: Add a second frap between each leg gap and re-dress knots. Check that legs are similar diameter at the head.

- Cord too slick or wet: Switch to bank line, add a constrictor start/finish, or insert a twig under the final half hitch to jam it.

Field Uses and Next Steps

This minimal-cord lashing builds cook tripods, lantern stands, game poles, and drying racks without burning through your line reserve. The key: neat, tight wraps and aggressive fraps. In the next section, we’ll open the legs to a stable stance and add a simple, adjustable pot hanger that won’t chew your cord or your patience.

Standing the Tripod Like a Pro: Leg Splay, Apex Angle, and Footing Tricks to Maximize Stability and Load

Standing the Tripod Like a Pro: Leg Splay, Apex Angle, and Footing Tricks to Maximize Stability and Load

You’ve got stew for four and three liters of water on the boil. A gust hits the camp and your pot swings. This is the moment you find out whether your tripod was stood with intention or just “good enough.” Stability isn’t luck—it’s geometry and ground contact. Get those right and a light lash with three sticks will safely carry a heavy, moving load all night.

Dial in the Leg Splay (Footprint)

Aim for an equilateral footprint—three feet forming a triangle with roughly equal spacing. For a typical cooking height of 110–140 cm (apex to ground), a base “diameter” (distance across two farthest feet) of 90–120 cm is a sweet spot. Quick rule: base radius ≈ 0.4–0.6 of working height. Wider splay lowers the apex and boosts lateral stability, but increases outward thrust at the feet.

How to set it:

– Start with the legs together, then open them evenly until the pot hangs over the center of the triangle.

– Hang your empty pot or a plumb line from the apex. The line should fall inside the triangle’s centroid—about a hand-width inside from each edge.

– Kick-test: push the apex sideways with two fingers. If the feet skate, deepen their seats (see footing tips) or widen slightly.

Why it matters: A too-narrow base makes the tripod tippy, especially when the pot swings. Over-splaying increases outward thrust and foot slippage, especially on slick ground.

Apex Angle and Load Path

Think in terms of leg lean: keep each leg about 15–25 degrees off vertical for cooking loads (2–8 kg including pot). That range keeps compressive force mostly down the legs while limiting outward thrust. More lean (30°+) amplifies kick-out risk; less lean (near vertical) gets tall and twitchy.

How to read it without a protractor:

– If your base radius is about half your height, you’re roughly in the 25° zone.

– Watch the lash: when opened, you should see a small, even gap between the leg tops—about a fist-width—indicating the lashing is bearing correctly and not binding.

Why it matters: The load splits into compression down each leg and outward thrust at the feet. As the legs lean more, compression and outward push both rise. Keep angles moderate and the lash tight (add 2–3 frapping turns) to lock the apex and prevent creep.

Common mistakes:

– Standing it too tall and narrow for the leg length.

– Letting the apex “settle” as the lash tightens, which drops your height and changes your angles mid-cook. Preload by gently leaning into the legs as you frap the lashing.

Footing on Real Ground

Your tripod fails at the feet, not the apex. Treat them like anchors.

- Firm soil: Twist each foot into a shallow divot 2–3 cm deep. Stomp-tamp the surrounding soil.

- Sand: Bury each foot 8–10 cm and tamp, or lash a small stick crosswise at each foot as a “sand shoe.”

- Snow: Lash 10×20 cm plates or flat sticks 10–15 cm above each foot as deadmen; set them broadside to the triangle’s center.

- Rock/slab: Place each foot on a flat stone with a bark or cloth pad for friction. Add a “base ring”—a cord loop around two legs 20–30 cm above ground—to limit splay.

- Mud: Use flat stones or split rounds as pads; seat feet slightly in and tamp.

- Slope: Put two legs uphill, one downhill. Extend the downhill leg slightly farther out to keep the apex plumb over center.

Troubleshooting:

– Feet creeping outward? Narrow the splay a touch, deepen sockets, add a base ring, or improve friction under the feet.

– Pot swings too much? Shorten the hanger so the pot sits lower (knee to mid-thigh height off the ground), or add a light windbreak.

Key takeaway: Match your base width to your height (0.4–0.6 ratio), keep leg lean in the 15–25° zone, and anchor the feet to the terrain you have. Nail those three, and the load will feel lighter, the swing will be tame, and the tripod will stay put. Next, we’ll rig the hanger so your pot sits exactly where you want it without fighting the fire.

Pot Hanger Systems with Almost No Cord: Toggles, Trammels, and Notched Hooks for Height Control

Picture this: the stew’s finally rolling, but a gust kicks the fire hotter and suddenly you’re boiling off your dinner. You’ve only got a foot of cord to work with and you can’t spare time for knots. This is where low-cord hanger systems shine—quick, secure adjustments with simple woodwork and a single loop.

The Loop-and-Toggle Strop

Start with a 12–18 inch loop of 2–3 mm cord (bank line resists heat better than fluffy paracord sheaths). Girth hitch that loop around the tripod hub so the “strop” hangs centered. Carve a toggle: 3–4 inches long, 1/2–3/4 inch thick, from green hardwood (hazel, maple, birch). Round the ends and leave a subtle waist so it sits without rolling.

Why it works: the toggle spreads load across the loop and keeps cord out of the heat. To use, twist the strop once to create two lobes, push the toggle through both, then let the twist cinch under load. The toggle becomes your anchor point—fast on, fast off—while the cord stays high and cool.

Troubleshooting:

– Toggle too skinny or short will lever out. Aim for thumb-thick and palm-length.

– Loop too long drops the toggle into heat. Keep the toggle 8–10 inches below the hub and well above flame tops.

– Melty synthetics: if you must use paracord, keep it higher and consider a small greenwood shield stick above the flame as a heat baffle.

The Trammel Hook: Adjustable Without Knots

Now add height control. Cut a straight green stick 18–24 inches long, 3/4–1 inch in diameter. Carve a J-hook on the bottom end for your pot bail—leave a 1/4 inch shoulder above the hook so the bail can’t ride off. Along the spine, carve a ladder of “saddle” notches every 1.5–2 inches: shallow hourglass cuts about 1/3 the stick’s thickness with defined shoulders. Smooth the rest; remove bark so heat doesn’t blister it loose.

Hang it by sliding your toggle into one of the notches. To adjust, lift the pot slightly, pop the toggle to a higher or lower notch, and set it back down. Each notch gives a predictable drop—roughly the spacing you cut—so you can go from rolling boil to steady simmer in two moves.

Why it works: the toggle bears against wooden shoulders, not cord or knots. Green hardwood resists scorching, and the load path is clean—no slipping hitches to creep.

Common mistakes:

– Over-cutting notches weakens the spine—stay shallow and crisp.

– Using dead, checked wood invites snap-offs. Green wood flexes.

– Notch edges too rounded let the toggle walk out. Keep shoulders square.

– Hook grain running out at the tip leads to breakage; carve the J so grain runs continuous through the curve.

Notched Fork Hook + Micro-Adjust Windlass

If time’s tight, a forked branch (about 1 inch diameter) makes a quick hook. Trim one tine short so the longer tine cradles the bail, leaving a 1/4 inch retaining nub. Cut two or three shallow steps along the back as backup notches for your toggle.

Need fine adjustment between notches? Use a Spanish windlass in the strop: slip a pencil-thick twig through the loop above the toggle and twist to shorten. Park the stick against a tripod leg or half-hitch it so it doesn’t unwind. This gives 1/2-inch micro-moves without re-carving.

Watch-outs:

– Over-twisting can snap thin cord—stop when the fibers sing, not scream.

– Keep the windlass above the heat line and away from the pot’s radiant zone.

Key takeaway: a short strop, a stout toggle, and a notched trammel give you fast, stable height control without burning cord or burning dinner. In the next section, we’ll marry these hangers to fire management—reading flame zones and setting pot height for efficient cooking.

Field-Proofing the Setup: Preventing Slippage, Managing Heat and Steam, and Weather Hardening

A squall pushes in mid-stew, wind skirting the fire and droplets hissing off the lid. This is where a textbook tripod either proves itself or dumps dinner. Field-proofing is about tiny choices—angles, notches, and cord path—that keep everything calm when the weather and heat aren’t.

Preventing Slippage at the Tripod and Hanger

Slippage starts at two places: the apex lashing and the pot interface. Build friction into both. Before lashing, score a shallow 1/8-inch ring notch around each leg where the cord sits. Those micro-shoulders prevent the entire apex from migrating under load. Use a standard tripod lashing: 6–8 wraps around all three legs, then 2–3 tight frapping turns between pairs until the cord “sings.” Why it works: frapping converts slack into compressive force, keeping the legs biting against each other. Pre-stretch synthetic cord (paracord/bank line) once before tying; wet cord relaxes and otherwise loosens as it dries.

Set your leg spread to a stable 55–65° and sink each foot 3–4 inches in soil or a few inches into packed snow. On sand or mud, lay a fist-sized flat rock or a short cross-stake under each foot to increase bearing surface. If the site is gusty, lay the upwind leg slightly more vertical and run a guyline from the apex to a stake 2 feet out.

At the hanger, slippage is solved by geometry. Cut a shallow V-notch (a “beak”) at the end of your greenwood hanger to seat the pot bail; depth 1/4 inch is plenty—deeper weakens the stick. Add a crosswise toggle (2.5–3.5 inches long) below the bail on a short loop so the bail can’t creep off the notch. If the pot still swings, shorten the hanger or add a second stabilizing line from the hanger to the downwind leg.

Common mistakes:

– Running the pot loop directly over the apex cord—heat plus motion melts knots.

– Splaying legs too wide, which lowers the apex and increases sway.

– Over-notching the hanger, inviting breakage.

Managing Heat, Flame, and Steam

Heat control is cord survival. Keep the apex at least 12 inches above the pot lid and route all cordage away from the heat column. If you must run a line near heat, sleeve it with a 4-inch wrap of wet bark or a green stick “standoff” so radiant heat hits wood, not synthetic. Maintain a pot height 6–8 inches above coals for a vigorous simmer without boil-over.

Steam burns faster than flame. Always lift the lid away from you and crack it downwind; place the lid so condensed steam drips outside the pot, not onto the hanger where sudden wetting can shock thin greenwood. Use a dedicated “steam stick” to nudge the lid or bail. If your pot likes to roll its bail to one side, wedge a small pebble between bail and handle to keep the center-of-gravity under the hanger notch.

Troubleshooting:

– Boil-over? Raise the pot an inch, widen the coal bed, and partly offset the pot from the fire’s hottest core.

– Sooty flare licking the cord? Shorten the hanger and rebuild the fire as a lower, wider bed.

Weather Hardening for Wind, Rain, and Snow

Rain swells natural-fiber cord and slicks bark. Back up your primary knots with a half hitch and retension after five minutes of wet. In continuous wind, add a windward guyline and widen the stance by 2–3 inches. In snow, stamp a platform, let it sinter for a minute, then plant legs; bank snow around each foot for a cold “cast.”

Cold and wet also expose material weaknesses. Favor green hardwood for the hanger (thumb-thick, no cracks) and seasoned, straight branches for legs. UV-baked paracord near flame is a short road to failure; if you have wire or a steel S-hook, use it for the final connection as a heat-proof link. No metal? Use a fresh green toggle and replace it once it dries and shrinks.

Key takeaways: build friction with notches and frapping, keep cord out of the heat column, and widen/anchor intelligently for weather. In the final section, we’ll break down teardown, pack-out, and leave-no-trace refinements so you can reuse the rig—or vanish it—without scarring the site.

Scaling Up and Adapting: Multi-Pot Kitchens, Uneven Terrain, and No-Cord Alternatives When You’re Short on Gear

You crest a wind-scoured ridge at last light—cold, hungry, short on cordage—and you still need to feed two people. The beauty of a tripod is that it scales. With a few smart tweaks, the same three-stick foundation can run a two-pot kitchen, stand steady on lumpy ground, or even go cord-free when your kit’s down to lint and willpower.

Multi-Pot Kitchens: One Frame, Two Meals

- The gallows bar: After you’ve set a solid tripod, suspend a horizontal green stick (24–36 in long, 1.25–1.75 in diameter) beneath the apex as a “gallows bar.” If you have only a short cord, make a simple timber hitch around the bar, then a turn around the apex bundle, finishing with a half hitch and a 4–5 in toggle to lock. Why it works: a centered bar distributes weight across all three legs. Hang two 2–4 L pots near the legs, not dead center, to reduce sag.

- Forked-yoke, zero extra cord: Carve a shallow 1/4 in shoulder 2 in from each end of the gallows bar. Wedge a forked stick (a Y about 8–10 in long) into the tripod apex, mouth down, then seat the gallows bar in the fork. The shoulders keep it from walking sideways.

- Clearances: Run pot lips 10–14 in above flame tips for steady simmering; raise to 16–18 in for slow cooking or when burning resinous softwoods.

- Troubleshooting: If the bar creeps, deepen the shoulders slightly or rotate the fork so the branch crotch bites the bar. If the apex twists with two pots, spread the legs wider and lower the apex 4–6 in to tighten the footprint.

Uneven Terrain: Make Gravity Your Ally

- Foot placement: Set the tallest leg downhill. Drive its foot 1–2 in into the soil or chock it with a fist-sized rock. On bedrock, notch each foot with a shallow V so it bites. Keep the apex directly over the fire’s center; sight from above.

- Leg angles: Aim for a 20–30° splay from vertical. On steep ground, shorten the uphill pair by shifting their feet closer to the fire rather than lowering the apex too far—this preserves pot height and stability.

- Quick leveling: If the pot swings into the slope, move the apex 2–3 in toward the uphill side. Re-check pot clearance; adjust hangers rather than chasing level by over-splaying legs.

- Common mistake: “skiing” legs on wet clay. Fix by roughing the feet with your knife, bedding them on bark, or trenching shallow heel stops.

No-Cord Alternatives When You’re Truly Short on Gear

- Green withy collar: Cut a thumb-thick willow/spruce withy 4–5 ft long. Wrap the three leg tops together three times, insert a 4–6 in toggle under the wraps, and twist to tension (Spanish windlass style). Tuck the tail. Re-wet if it dries and loosens.

- Bark and roots: Basswood/linden inner bark or spruce roots (pencil-thick) soaked 10–20 minutes make excellent emergency lashings. Use 4–6 tight turns and two frapping turns; finish with a jam under the wraps.

- Wedge-lock apex (no lashings): Cut a shallow 1/4 in groove around each leg 3 in from the top. Bind the three with a pliant sapling strip in a tight ring, then hammer in a hardwood wedge between two legs under the ring. The ring and wedge act as a cam, locking the bundle.

- Pitfalls: Dry withies snap—choose fresh, bendable growth. Bark strips shrink as they dry; counter by adding a second toggle twist after 10–15 minutes of heat exposure.

Key takeaways: Put weight near the legs, not the void; tune pot height to your fire, not vice versa; and when cordage is scarce, nature’s fibers and smart wedges keep your kitchen standing. With these adaptations, three sticks become a full-service camp kitchen—even when the ground tilts and your cordage budget’s down to zero.

Three sticks and a short cord can be a stove, a drying rack, a lantern stand—whatever the moment demands—if you understand the why behind each move. Choose poles that are straight, shoulder-thick for heavy pots (1.25–2 inches), and long enough to give a wide, confident stance. Lash deliberately: tight wraps, firm fraps, a fist-wide hinge at the apex. Stand it smart: feet set on mineral soil, legs splayed until the structure “locks,” apex over the heat, and the heaviest load tested at double the expected weight before you hang dinner.

Here’s your next field drill:

– Build a backyard tripod with three 5–6 ft poles and 4–6 ft of 3–4 mm cord. Time yourself from first wrap to hanging a 2-liter water bottle—aim for under 3 minutes.

– Make three hangers: a 4–6 inch toggle; a trammel with 1-inch notch spacing; and a green-wood hook with a deep, back-cut notch. Practice height changes with gloves on.

– Stress-test: widen the stance for a full pot, then gust it with a tarp to check wind stability. If a leg skates, reset feet, rotate the bark side down, and add one more frap.

– Rain rehearsal: wet your cord. Note how natural fibers bite and synthetics slip; adjust with an extra wrap or a half-hitch on the standing line.

– Build a “tripod kit” bag: cord pre-marked for wrap count, a spare toggle, and a pre-notched trammel stick.

Master this and you’ll never be waiting on gear to cook, boil, or rig a camp task. It’s light, fast, and scalable—and it makes you the person others trust when flame, food, and time matter.