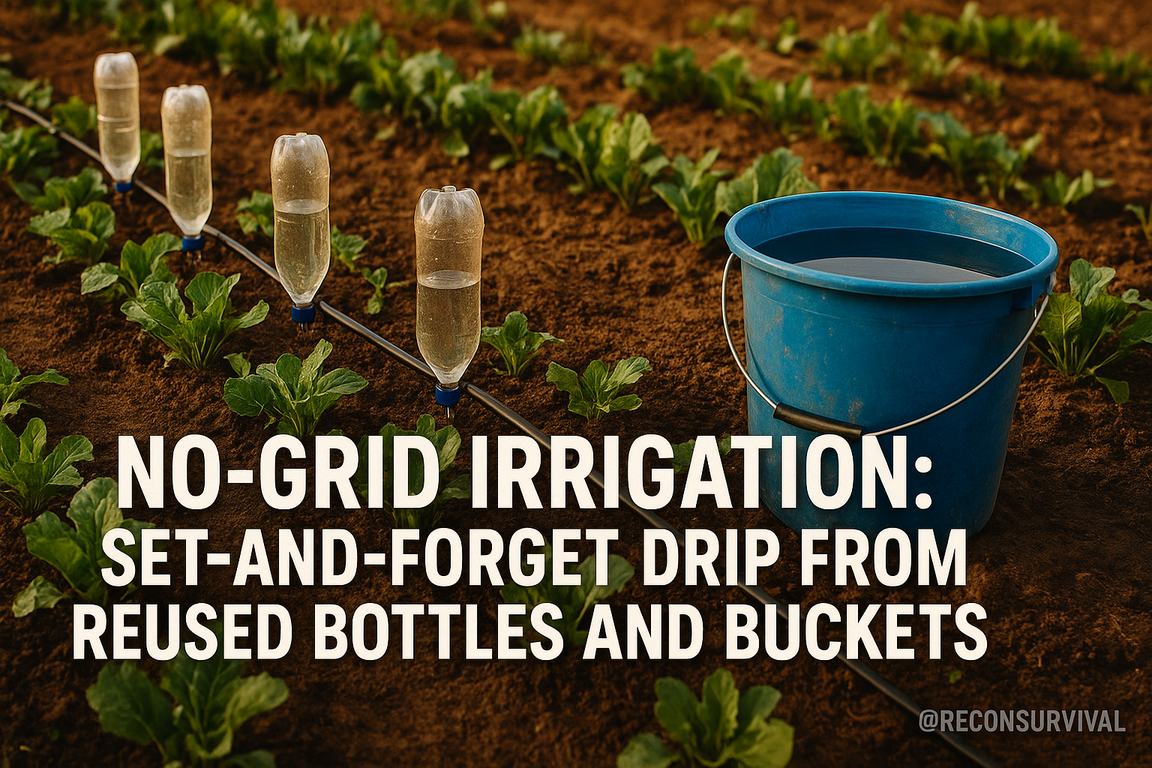

By the third straight day of 100-degree heat, the city’s water pressure hiccuped, your timer blinked 12:00, and the peppers drooped like flags at half-mast. No power, no pump, no schedule—just thirsty soil and the clock running hot. Here’s the good news: your irrigation doesn’t need electricity, moving parts, or pricey emitters. It needs gravity, a few reused containers, and the right small holes in the right places.

I’ve kept beds alive through weeklong heat waves and grid hiccups using soda bottles, five-gallon buckets, and scavenged tubing—systems that watered precisely while I was miles away. The math backs it up: vegetables need about 1 inch of water per week (roughly 0.62 gallons per square foot). Drip targeted at the root zone typically cuts that requirement by 30–50% compared to overhead watering. With a couple of cinder blocks for elevation and a handful of humble vessels, you can meet that need quietly and predictably—even if the lights stay out.

This guide will show you how to build set-and-forget, no-grid drip from reused bottles and buckets that won’t clog, flood, or run dry too soon. You’ll learn the simple physics (head pressure, flow, and wicking), how to size and place emitters for different crops, and the tweaks that separate a clever hack from a season-long solution. We’ll cover filtering and algae control, anti-siphon vents, cold-weather considerations, slope and elevation tricks, and real troubleshooting: vacuum lock, slow drips, runaway leaks, and critter damage. You’ll get step-by-step builds, exact drill sizes, flow-rate targets, and test methods you can do with a measuring cup and a stopwatch.

If you’ve got buckets, bottles, and a garden that insists on water whether the grid cooperates or not, read on. This is irrigation that works while you’re gone.

How Gravity Feeds a Garden: Flow, Head Height, and Soil Infiltration for Off-Grid Drip

You’re a week into a hot spell. The rain barrels are low, the grid’s been twitchy, and the tomatoes don’t care about your power situation. You set a 5-gallon bucket on a couple of cinder blocks, run thin lines down to the plants, and walk away. The magic here isn’t magic at all—it’s gravity, head height, and soil that can actually take the drink you’re pouring.

Head Height: Your “Pressure” Without a Pump

Gravity-fed drip lives or dies on head height—the vertical distance from the water surface in your reservoir to the emitter. That height translates to pressure. The conversion is simple and worth memorizing:

– Every 2.31 feet (0.7 m) of vertical head ≈ 1 psi

– Or roughly 1 foot (30 cm) ≈ 0.43 psi, 1 meter ≈ 1.42 psi

Why it matters: flow through a small hole or tube increases with the square root of pressure. Double the head height and you don’t double the flow—you boost it by about 41% (sqrt of 2). That’s enough to turn a lazy drip into a steady one.

Actionable example: A 5-gallon bucket on a 3-foot stand gives you about 1.3 psi at the start. As the bucket drains, the water level drops, head decreases, and flow tapers. That’s normal—plan for it. Use taller, narrower reservoirs (stacked buckets or a 20–30 L jerrycan) to keep head more consistent as they empty.

Common mistakes:

– Measuring from the bucket’s outlet instead of the water surface.

– Running lines uphill: any emitter higher than the reservoir’s water line won’t flow.

– Overloading one reservoir with too many emitters for the available head.

Flow and the Soil You’ve Got

The right drip rate isn’t just “slow”—it’s matched to your soil’s ability to absorb water.

Typical infiltration rates:

– Sandy: 1–2 inches/hour (25–50 mm/hr)

– Loam: 0.5–1 inch/hour (12–25 mm/hr)

– Clay: 0.1–0.3 inch/hour (2–8 mm/hr)

If your emitters outrun infiltration, you get surface pooling, runoff, and wasted water. Too slow, and the top dries while deeper roots get nothing.

Quick field test: Press a bottomless 4-inch can or short length of 4-inch PVC 2 inches into the soil. Add 1 inch (25 mm) of water and time how long it takes to disappear. That gives you a ballpark infiltration rate for adjusting your drip.

Real-world sizing: Say you hang a 5-gallon (19 L) bucket 3 feet up feeding eight DIY emitters. If each emitter delivers 100 mL/hour, that’s 0.8 L/hour total—your bucket lasts ~24 hours. For a 4×8 ft bed needing roughly 1 inch/week (~20 gallons/76 L), you’d run that setup about 4 days/week or increase head/emitter size for shorter daily runs.

Troubleshooting the Flow

- Air locks: Keep a vent. Buckets can be lidded to block algae, but don’t seal them airtight. Bottles buried as emitters need a tiny air hole high on the bottle; no vent equals vacuum and no drip.

- Clogging: Silt and algae are the enemy. Pre-filter with a scrap of T-shirt or coffee filter under the lid. Keep containers opaque or wrapped to choke algae.

- Inconsistent output: Uneven terrain or mixing line diameters can starve far emitters. Use equal-length laterals when possible and keep lines gently sloped downward.

Key takeaways: Head height is your pressure, and soil sets your speed limit. Measure head from the water surface, match flow to infiltration, and expect drip to taper as reservoirs drain. Next up, we’ll turn scavenged bottles and buckets into reliable emitters—and show you how to “set and forget” the flow they deliver.

Smart Scavenging: Safe Reuse of Bottles, Buckets, and Tubing (Cleaning, Sizing, and Prep)

You’ve just hauled home a stack of 2-liter bottles, a sun-faded 5-gallon bucket, and a coil of mystery tubing from a yard sale. Perfect fodder for a no-grid drip system—if you prep it right. Smart scavenging isn’t just about what you can get for free; it’s about what won’t poison your soil, clog in a week, or crumble in the sun.

Choose Safe Plastics and Containers

- Plastics to favor: PET/PETE (#1) for bottles, HDPE (#2) for buckets/jerry cans, and PP (#5) for caps/fittings. These are common in food packaging, tough enough for low-pressure water, and generally garden-safe.

- Plastics to avoid: PVC (#3) for water carry (possible plasticizers), polycarbonate (#7) if unknown, and anything that held automotive fluids, pesticides, or solvents. If you don’t know what lived in it, don’t irrigate with it.

- Real-world picks: 2-liter soda bottles as emitters; 1–5 gallon HDPE buckets or camping jugs as reservoirs. Aquarium or irrigation-grade polyethylene micro-tubing is best; silicone tubing is a good second. Skip vinyl tubing if you can.

Why it matters: Food-grade plastics are less likely to leach nasties and hold up better under UV and mechanical stress, and you can get them everywhere.

Deep Cleaning and Sanitizing

- Strip labels/adhesives with warm water and a dab of cooking oil or isopropyl alcohol. Avoid solvents that can craze plastic.

- Wash: hot water + a few drops of unscented dish soap. Use a bottle brush to reach seams.

- Sanitize: 1 tablespoon of unscented household bleach (5–6% sodium hypochlorite) per gallon of water. Fill, swish, and let contact for 2 minutes. Rinse thoroughly. Alternative: 1 cup of 3% hydrogen peroxide per gallon, 10-minute contact, then rinse.

- Tubing: pull a length of weed-whacker line or paracord through as a “snake” wrapped with a small rag to scrub biofilm. Flush with the same sanitizing solution, then clear water.

Common mistakes: Mixing vinegar and bleach (toxic gas). Using hot water that warps thin bottles. Trusting smell alone—residues can be odorless.

Sizing and Prep: Caps, Buckets, and Tubing

- Caps and feed-throughs: For a simple emitter, a heated needle (think 18–20 gauge; ~1 mm) through a PET cap yields a slow drip. For more control, drill a 1/4-inch hole and insert a 1/4-inch barbed adapter with a rubber washer (cut from a bicycle inner tube) inside the cap; snug with a nut or gasket.

- Drill tips: Use a brad-point or step bit on low RPM. Support the plastic with scrap wood. Run the bit backward to score before drilling forward to prevent cracking. Deburr with a utility knife.

- Buckets as reservoirs: Install an outlet near the bottom. Test-fit your grommet/barb combination on scrap first; hole sizes vary by grommet brand. A bead of silicone on the outside helps seal micro-weeps.

- Tubing sizes: 1/2-inch mainline (polyethylene) from the bucket, stepping down to 1/4-inch OD micro-tubing for emitters is a reliable combo. Salvaged tubing? Measure with calipers; you want snug, not forced. Warm the tube end in hot water for easier barb insertion.

Why sizing matters: Flow depends on head pressure (about 1 psi per 27 inches of water height) and restriction. Oversized holes dump water; too small clogs easily. Controlled interfaces—barbs, grommets, and consistent tubing—mean repeatable results.

Light-Proof and UV-Protect

- Algae thrives in light. Paint bottles and buckets matte black or wrap in opaque tape or foil. Use black tubing or bury/cover lines with mulch.

- UV kills plastics. Keep reservoirs out of direct sun if possible, or shade with scrap plywood or fabric.

Troubleshooting and Pitfalls

- Leaks at fittings: Upgrade to a slightly larger barb or add a washer inside and out. Don’t overtighten caps; it warps seals.

- Flow too fast: Step down hole size (use a smaller needle) or add an inline clamp/valve. Lower the reservoir to reduce head.

- Flow too slow: Raise the reservoir 24–36 inches, ensure no kinks, and clear emitter holes with a fine needle.

- Cloudy water/algae: You’ve got light leaks. Opaque wrap and a fresh sanitizing rinse fix most issues.

Key takeaway: Start with food-safe plastics, clean like you mean it, and size your interfaces thoughtfully. With the hardware prepped and light-proofed, you’re ready to design a gravity-fed layout that delivers steady drips without babysitting—next up, dialing in head height and flow control.

Bottle Emitters That Actually Work: Pin-Hole, Wick, and Dripper-Cap Builds with Measured Outputs

You’ve got seedlings in, a heat wave on the calendar, and only evenings to check the beds. This is where bottle emitters pay their rent—quietly pushing steady moisture to the root zone without a power source or timer. The trick is building emitters that are predictable, clog-resistant, and measurable. Here are three field-proven builds you can dial to deliver exactly what your plants need.

Pin-Hole Emitters: Fast to Build, Easy to Calibrate

Why it works: A tiny orifice controls flow by restricting water under low head pressure. Great for short, moderate outputs.

How to:

– Use a clean 1–2 L PET bottle. Heat a fine sewing needle and pierce a single hole in the cap from the inside out to minimize burrs. Start tiny—about 0.3 mm.

– Add a micro-vent: a second pinhole in the bottle bottom (now the top when inverted). This prevents “glugging” vacuum lock and keeps flow steadier.

– Invert and bury the cap 3–5 cm deep near the root zone; shade with mulch to cut algae.

Measured outputs (tested with a 2 L bottle, ~20 cm head, 20–25°C):

– 0.3 mm hole: roughly 0.7–1.0 L/day average as the head declines.

– 0.5 mm hole: roughly 2–3 L/day average; can overshoot in sandy soils.

Troubleshooting:

– Too fast? Melt the cap hole slightly closed with a hot needle or swap caps and try smaller.

– Inconsistent drip? Add the micro-vent or reduce head by laying the bottle at a 30–45° angle.

– Clogging: Pre-filter water through a bandana. If flow fades, poke the hole clear from the inside out.

Key takeaway: Pin-holes are your “set for a heatwave” tool—simple and consistent if you control hole size and venting.

Wick Emitters: Ultra-Slow, Root-Friendly Seep

Why it works: Capillary action pulls water along fibers at a near-constant rate, largely independent of head. Ideal for seedlings and moisture-sensitive beds.

How to:

– Drill a snug hole in the cap and thread a pre-soaked cotton sash cord or mop strand (5–8 mm). Knot inside to prevent slip. Polyester/acrylic works but is slower unless braided.

– Extend 10–20 cm of wick into the soil, bent into a shallow “J” to keep end buried 5–8 cm.

Measured outputs (1–2 L bottle, wick length 25 cm):

– 5 mm cotton: about 0.3–0.6 L/day.

– 8 mm cotton: about 0.8–1.5 L/day.

Add a second wick to double output; shorten wick or use thinner fiber to reduce.

Troubleshooting:

– No flow? Synthetic wick not wetted—pre-soak in warm water with a drop of soap, then rinse.

– Dying off mid-season? Salt/mineral crust on wick—trim 1–2 cm off the soil end and re-seat.

– Evaporation loss: Keep wick end buried and mulched.

Key takeaway: Wicks excel for steady micro-delivery where a pin-hole would overshoot.

Dripper-Cap Builds: Adjustable and Measurable

Why it works: A tiny valve and tube give you a tunable orifice and a convenient way to count drops, turning any bottle into a calibrated dripper.

How to:

– Drill a 4–5 mm hole in the cap. Press-fit a 1/4″ barbed aquarium valve or RO valve; seal with silicone if loose.

– Push 20–30 cm of 3–4 mm ID silicone tube onto the valve; pinch-cut the tube end at 45° for clean drops.

– Invert bottle and stake tube tip at root zone.

Calibration:

– Open until you get visible drops. Count drops for 30 seconds.

– Rule of thumb: 20 drops ≈ 1 mL. So 1 drop/sec ≈ 180 mL/hour ≈ 4.3 L/day. One drop every 5 seconds ≈ 0.86 L/day.

– Set per plant: peppers 0.5–1 L/day; tomatoes 1–2 L/day; squash 1–3 L/day depending on soil and heat.

Troubleshooting:

– Drift with temperature: Recheck after hot afternoons; viscosity changes can bump flow. Shade the bottle/valve.

– Air leaks around the valve? If drip stops and line drains, reseal the cap bulkhead and make sure the vent is tiny, not a draft.

– Sediment: Add a short bit of nylon stocking inside the cap as a pre-filter.

Key takeaway: Dripper-caps give you “knob control” in the field. Count drops, set once, and you can predict watering to within a few hundred milliliters per day.

Dial in one style per bed, or mix them—pin-holes for thirsty vines, wicks for seedlings, dripper-caps for finicky perennials. Next, we’ll scale these emitters to bucket reservoirs so you can run a whole row from a single fill.

The Elevated Bucket Reservoir: Setting Up Headers, Simple Manifolds, and Passive Flow Control

The Elevated Bucket Reservoir: Setting Up Headers, Simple Manifolds, and Passive Flow Control

A July afternoon. Power’s out, the hose is dry, and the sun’s got your tomatoes on the ropes. You step onto a milk crate, crack the valve on a bucket perched four feet up, and hear that soft hiss of water finding every root. That’s the promise of an elevated reservoir: simple gravity doing quiet work for days at a time.

Why Elevation Matters

Gravity gives you pressure. Rough rule: each foot of height adds about 0.43 psi. A bucket outlet 4 feet above the bed gives roughly 1.7 psi—plenty for gravity-rated drippers, short microtubes, or pinhole emitters, but not enough for most pressure-compensating hardware that expects 10+ psi. The higher the bucket, the more consistent your flow and the more lines you can feed—within reason. Keep runs short and diameters sensible, and you’ll get even distribution without a pump.

Building the Reservoir and Header

Start with a 5-gallon (20 L) food-grade bucket. Paint or wrap it dark to block light (algae steals oxygen and clogs lines). Drill a 3/4-inch hole 1.5 inches above the bottom and install a 1/2-inch bulkhead fitting with a short 1/2-inch ball valve. Why above the bottom? You leave a silt sump so your last pint isn’t a grit smoothie.

Set the bucket 3–5 feet above the highest emitter—on a shelf, sturdy tripod, or stacked blocks. Secure it against wind. On the outlet, push on 1/2-inch poly mainline. This becomes your header. Keep any single header under 25–30 feet for low-head systems, and try to route it level. A ring manifold around a bed equalizes pressure better than a dead-end line.

Add a simple filter: a 200–400 micron paint strainer bag under the lid or a short inline Y-filter if you have one. A debris-free header is the difference between “set-and-forget” and “hunt-and-poke.”

Simple Manifolds That Don’t Clog

From the 1/2-inch header, punch barbed 1/4-inch tees to create takeoffs every 12–24 inches. Run 1/4-inch microtubing (keep each under 6–8 feet) to each plant. At the plant end, choose one of three gravity-friendly emitters:

– Pin-hole buttons or gravity drippers rated 0.5–2 L/hr

– Short microtube “orifices” (1–2 inches of 0.020–0.030-inch ID tube as a restrictor)

– DIY pin-prick in a short cap of tubing, backed by a tiny inline valve

Real-world numbers: A 5-gallon bucket at 4 feet head feeding 16 peppers via microtube restrictors delivered ~0.75 L/plant/day in 90°F weather and ran 40 hours before refill. Scale by raising the bucket, adding a second bucket in parallel, or lengthening the restrictors to reduce flow.

Passive Flow Control Without Electronics

Two passive tools do the heavy lifting: head height and orifice size. Height is your throttle; 6 inches of change is noticeable. Orifice size is your jet; smaller holes smooth out differences but clog more easily, so filter well.

Add simple in-line 1/4-inch valves (aquarium-style works) at each takeoff for fine-tuning. For steadier distribution, loop the header into a ring, and install a flush cap at the lowest point for periodic blowouts. Want more consistency as the bucket drains? Use a standpipe inside the bucket: a short vertical tube attached to the bulkhead sets the minimum water level, keeping “active head” constant until the level drops to the standpipe top, then flow stops cleanly instead of tapering to a trickle.

Troubleshooting and Common Mistakes

- Bucket too low: If lines starve at the far end, raise the reservoir or shorten the header. Aim for 3–5 feet of head.

- Wrong emitters: Pressure-compensating drippers won’t open on gravity. Use gravity-rated buttons, microtubes, or pinholes.

- Algae and slime: Clear tubing or uncovered buckets breed clogs. Opaque everything; filter always.

- Airlocks: If flow sputters after a refill, crack the highest valve briefly to vent trapped air.

- Overloading one header: More than ~20 outlets from a single 1/2-inch gravity header invites uneven flow. Split zones or add a second bucket.

- Leaky fittings: Lubricate barbs with water, use proper punch tools, and seat bulkheads snug—not gorilla tight—so you don’t distort gaskets.

Key takeaway: Elevation plus a clean header and simple manifold gives you reliable, passive irrigation. Next, we’ll dial in plant-side emitters and scheduling so each crop gets exactly what it needs without babysitting.

Layout That Waters Itself: Zoning Beds, Burying Lines, Mulch Integration, and Tuning for Crops

Layout That Waters Itself: Zoning Beds, Burying Lines, Mulch Integration, and Tuning for Crops

A late-July heat wave rolls in the same week you’re off-grid on a supply run. You return to find the tomatoes upright, the lettuces crisp, and the squash not sulking. That’s the payoff of a layout that waters itself—built around zones, buried distribution, and crop-specific tuning so gravity does the thinking while you’re gone.

Zone by Thirst, Not by Convenience

Group beds by water demand and soil type so each zone gets its own bucket or bottle network. Fruiting gluttons (tomato, pepper, cucumber) form a “heavy” zone; leafy greens and brassicas sit in a “moderate” zone; herbs and drought-hardy perennials get a “light” zone.

- Hardware: One 5-gallon bucket per 16–24 sq ft in heavy zones, per 24–32 sq ft in moderate zones, and per 32–48 sq ft in light zones. Elevate reservoirs 24–36 inches above soil to maintain steady flow (roughly 1–1.5 psi).

- Control: Split each bucket to 2–6 laterals with T-fittings and add cheap inline micro-valves or pinch clamps to balance lines. Keep zones physically separate so you can top off buckets on different schedules.

Why: Plants drinking at different rates on the same line force you into constant babysitting. Zoning lets you set a stable drip rate and leave it alone for days.

Common mistake: One big bucket feeding the entire garden. Pressure drops over distance and elevation create winners and losers. Break it up.

Bury the Lines Where Roots Actually Drink

Bury spaghetti lines and bottle necks shallow so water lands in the root zone, not the air.

- Depth: 2–3 inches below the surface for most soils; 1–2 inches in heavy clay to avoid perched water.

- Placement: For single plants, place emitters or bottle necks 6–8 inches from the stem, on the downhill side if on a slope. For rows, run a lateral 2–3 inches off the row with holes/emitters every 8–12 inches (greens) or 12–18 inches (tomatoes/peppers).

- Bottles: Bury 1–2 L bottles neck-down with 3–5 x 1 mm holes around the neck. Backfill firmly to prevent water from channeling up.

Why: Burial cuts evaporation, shields plastic from UV, and evens out soil moisture, reducing blossom end rot and tip burn.

Troubleshooting: If you see surface pooling, the holes are too large or depth too shallow—swap to fewer/smaller holes or bury 0.5 inch deeper. Dry streaks along the row? Increase emitter spacing density or add a second lateral.

Mulch Is the Silent Partner

Lay 2–4 inches of mulch over buried lines after you leak-test.

- Materials: Shredded leaves, straw, or pine needles for annual beds; wood chips for perennials. Keep a 2-inch bare “donut” around stems to prevent rot.

- Function: Mulch slows evaporation, prevents crusting (which repels water), and buffers temperature, stabilizing drip rates.

Common mistake: Mulching before testing. Lock in your layout wet, not dry, or you’ll chase ghosts. Also avoid mixing wood chips into annual bed soil—they rob nitrogen; keep chips on top.

Tune for Crops and Soil

Dial flow by plant, not just by zone.

- Tomatoes/peppers: One 1–2 L/h equivalent per plant or a single 1–2 L bottle refilled daily during peak fruit set. In sand, consider two emitters per plant.

- Greens: A lateral with holes every 6–8 inches delivering roughly 0.2–0.3 L/ft/hr keeps the top 6 inches uniformly moist.

- Melons/squash: Two emitters per hill, 8–10 inches from the crown, for a wider wetting pattern.

- Clay vs. sand: Clay spreads laterally—use wider spacing and lower flow. Sand drains fast—closer spacing and slightly higher flow.

Calibrate by catching output from one line into a measuring cup for 15 minutes. Multiply to get hourly flow and adjust bucket height or valve opening until a plant’s daily need matches your reservoir capacity.

Troubleshooting: Uneven rows on a slope? Run a loop (header connected end-to-end) to equalize pressure, and throttle the near-side valves slightly. Clogging? Add a cloth pre-filter inside the bucket outlet, paint or shade buckets to deter algae, and open line ends weekly to flush.

Key takeaway: Zone by need, bury for efficiency, mulch to lock it in, and tune to the plant and soil. With layout settled, the final step is long-term maintenance—keeping lines clear and the system winter-ready without grid help.

Keep It Running All Season: Maintenance, Troubleshooting Clogs, Algae Control, and Winterizing

A week into a heat wave, your tomatoes start to sulk even though the buckets are full. You pop a lid and catch that faint pond smell—biofilm has crept in, throttling flow. The fix isn’t heroic; it’s routine. Set-and-forget drip only stays “set” if you give it a few minutes of smart upkeep.

Fast Weekly Check: Verify Flow Before Plants Complain

- Five-minute cup test: Slip a 1-cup (237 ml) jar under one emitter per zone. In 5 minutes, you should collect roughly 15–40 ml from a 1 L/hr emitter (target ranges vary with head height). If it’s under half your normal, assume partial clogging.

- Inspect head height: As reservoirs drop, pressure drops. Keep outlet 24–36 inches above emitters for consistent flow. Mark “refill” at 1/3 full on the bucket.

- Flush line ends: Open the farthest cap 30–60 seconds until flow runs clear. Close gently—over-tightening splits caps.

Why: Small issues—sediment, air locks, pressure loss—compound silently. A quick test catches them before leaves curl.

Common mistakes:

– Poking emitters with metal pins (enlarges orifices). Use a wooden toothpick.

– Leaving clear bottles/buckets in sun (algae blooms). Wrap or paint them opaque.

Clog Troubleshooting: Sediment, Scale, and Slime

- Sediment: Install a 200-micron paint-strainer bag under the bucket lid. Rinse weekly. If you see grit in the flush, add a second bag as a sock over the outlet barb.

- Mineral scale (hard water): Soak emitters overnight in 1:1 white vinegar:water or 1 tbsp citric acid per quart. For lines, do a 10-minute acid flush at season’s midpoint: add 1 tbsp white vinegar per 5 gallons to the reservoir, run until you smell vinegar at the far end, then flush with clean water.

- Biofilm/algae: Dose the reservoir with 3% hydrogen peroxide at 1–2 ml per liter (roughly 1–2 tsp per gallon) every 1–2 weeks. Let it sit 30 minutes before irrigation. Safe for roots, hostile to slime.

Why: Each clog type responds to a different chemistry; guessing wastes time. Peroxide oxidizes organics, acids dissolve carbonate scale.

Pro tip: If one plant’s emitter lags while others are fine, swap that emitter with a known-good one. If the problem stays put, the line is fouled; if it follows, the emitter’s the culprit.

Algae and Mosquito Control Without Poisoning Your Soil

- Block light: Paint buckets with two coats of flat black or wrap with UV-resistant tarp. Keep lids on; vent with two 1/2-inch holes covered in mesh.

- Mosquitoes: Drop 1/4 of a Bti dunk per 5-gallon bucket monthly. Bti targets larvae, not your garden.

- Avoid bleach in reservoirs. If you need to sanitize removed parts, use 1 tbsp unscented bleach per gallon for 10 minutes, then rinse thoroughly.

Midseason Repairs and UV Watch

- Leaks: Hand-tighten hose clamps; add PTFE tape to threaded barbs. Replace grommets that feel brittle.

- Root intrusion: Keep emitters 1 inch above soil or sleeve with a 1×1-inch square of geotextile tied on with garden wire.

- Sun damage: Check tubing on the south side for microcracks. Replace suspect 6–12 inch sections now, not when they burst at noon.

Winterizing: Drain, Dry, and Don’t Crack Anything

Before first hard freeze:

– Drain everything. Open all line ends and tilt buckets to empty. Any trap of water becomes a splitter at 32°F.

– Blow out lines gently with a bicycle pump at 5–10 psi. Higher pressures can pop barbs.

– Soak emitters in vinegar, rinse, dry, and store in a labeled zip bag.

– Store buckets inverted and out of sun. If they must stay outside, leave them empty with lids on.

Key takeaways: Check flow weekly, shade and strain your water, match the fix to the clog, and prep for winter before frost. A few minutes now beats a garden on life support later.

Picture it at dawn: a quiet line of beds, a shaded bucket on a stand, and a slow, even drip already working while you’re still lacing your boots. That’s the payoff of pairing gravity with measured flow. The core remains simple: give the system a little head (every foot ≈ 0.43 psi), deliver water at the speed your soil can drink, and protect the water path from grit and sun. Clean, right-sized salvage, emitters you’ve timed in mL/min, and an elevated reservoir feeding short headers and zoned laterals under mulch—those are the levers that make “set-and-forget” real. Keep it clean (prefilter with a stocking, opaque reservoirs, occasional flush), keep it shaded, and drain before the freeze.

Make it move from idea to garden with a quick pilot:

- Choose one 4×8 bed. Mount an opaque 5-gallon bucket 3–4 feet high; add a bottom outlet and a simple header in 1/4-inch line with a stocking prefilter.

- Build two emitter types (pin-hole and wick). Aim for 1–2 mL/min per emitter (60–120 mL/hour); verify with a measuring cup and a stopwatch.

- Space laterals 12–18 inches apart, bury 2–3 inches deep, mulch 2–4 inches. Run 30–60 minutes, then probe moisture at 4–6 inches.

- Log outputs and plant response for a week; trim hole size, wick length, or head height to hit your crops’ needs (~0.6 gallons/sq ft/week as a baseline), then scale.

Avoid the usual tripwires—too little head, long flat runs, unfiltered water, sun-baked tubing—and the system will quietly buy you time and resilience. Build one bed that waters itself, and you’ll trust it to carry the rest—heatwaves, busy weeks, even a power outage. Water is life; let gravity do the lifting.