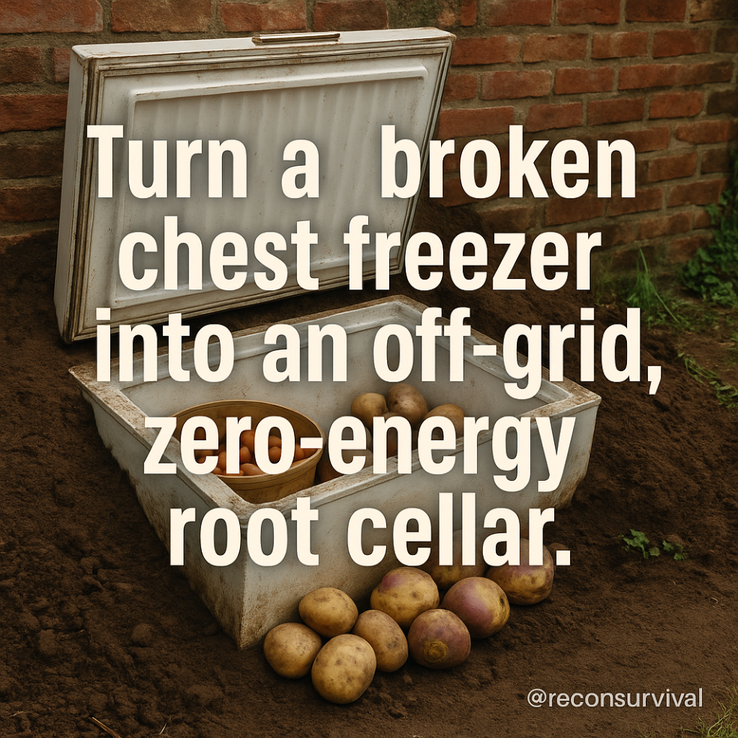

Picture this: the power’s out for days after an early ice storm, the stores are stripped, and your pantry is full of produce from the fall harvest. You can smell the apples softening and the potatoes sprouting. Now imagine stepping into the backyard, lifting the lid on a “dead” chest freezer set into the ground, and pulling out crisp carrots and firm Yukon Golds at 40°F—no electricity, no noise, no fuel. In a country where roughly 30–40% of food ends up wasted, turning a broken appliance into reliable, zero-energy cold storage isn’t just clever—it’s good stewardship of what we’ve been given.

I’ve converted more than a few failed chest freezers into off-grid root cellars over the years, and they’ve held 38–45°F with high humidity through shoulder seasons and deep winter alike. Done right, a repurposed freezer harnesses the earth’s stable temperatures and the unit’s own insulation to protect your harvest for months. Done wrong, it becomes a moldy bin or a summertime oven. The difference is in the details—choosing the right site, managing water, tuning airflow, and matching storage conditions to the specific needs of your crops.

In this guide, we’ll walk step-by-step through the build: site selection and utility checks, safe excavation, drainage and gravel beds, ventilation design that actually balances temperature and humidity, rodent-proofing and condensation control, and simple shelving that maximizes space. We’ll cover crop-by-crop storage targets, how to avoid ethylene cross-contamination, and seasonal adjustments so your cellar doesn’t freeze in January or sweat in August. You’ll see common mistakes, field-tested fixes, and a realistic bill of materials. Most of all, you’ll come away with a quiet, low-profile system that keeps food on the table and strengthens your household—and your neighborhood—when it matters most. Let’s make something enduring out of what the world calls broken.

From Dead Appliance to Cold Storage: Choosing the Right Chest Freezer, Site, and Tools for Your Climate

From Dead Appliance to Cold Storage: Choosing the Right Chest Freezer, Site, and Tools for Your Climate

You’ve got a “dead” chest freezer headed for the dump—big, insulated, and still weather-tight. With a little stewardship-minded ingenuity, that carcass becomes an off-grid, zero-energy root cellar that keeps carrots crisp and apples firm long after the first frost. The key is choosing the right unit, siting it smartly, and staging the right tools before you break ground.

Pick the Right Carcass

- Size: A 10–15 cu ft chest freezer suits most families, holding roughly 6–8 standard milk crates or 8–10 five-gallon buckets. Smaller (7 cu ft) units are great for singles or tight yards; 20+ cu ft is heavy and demands more digging.

- Construction: Prefer manual-defrost chests with intact lid gaskets and a solid interior liner (aluminum or heavy plastic). Check for floor rust, cracked hinges, or warped lids—those leak cold like a sieve.

- Sealed system: Do NOT cut refrigerant lines. If you need the compressor removed for space or weight, have an HVAC tech recover the refrigerant legally. Otherwise, leave the sealed system intact and out of the way.

- Cleanability: Moldy is manageable; rotten insulation is not. If the unit smells like old fish oil, it’s often leaked compressor oil—pick another.

Site Selection by Climate

- Drainage first: Choose high ground, not a swale. Keep at least 50 ft from septic and 100 ft from wells. Aim for the north or east side of a building for shade.

- Frost and heat: In cold climates (frost line 36–60+ inches), bury as deeply as practical and add a small above-lid shelter. Where full frost-depth burial isn’t realistic, add 2–4 inches of rigid foam over and around the lid area and plan to mulch seasonally. In hot climates, prioritize deep shade, maximize earth contact on sides, and avoid south-facing exposures that bake the lid.

- Water table: If you hit water within 24–30 inches, switch sites or raise the install with a French drain and a gravel pad.

Tools and Materials to Stage Now

- Digging: Spade, trenching shovel, mattock, digging bar; 4 ft level and tape.

- Drainage: 10–15 bags of 3/4″ crushed stone, landscape fabric, optional 10 ft of 3″ perforated drain pipe.

- Insulation and sealing: 1–2 sheets of 1–2″ XPS/EPS foam, exterior-grade silicone, butyl tape, aluminum flashing tape.

- Vermin/vent prep: 2–3″ PVC pipe, two 90° elbows, caps, and stainless hardware cloth.

- Protection: Heavy gloves, eye protection, and a dust mask for cleanup.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Setting in a low spot—your “cellar” becomes a cistern.

- Trusting a bowed lid—test with a flashlight inside; fix or replace the gasket.

- Ignoring climate—shallow installs in deep-freeze zones will frost your potatoes; shallow shade in hot zones will warm your beets.

Key takeaway: pick a sound freezer, a dry and shaded site, and gather drainage and insulation materials tailored to your climate. Next, we’ll prep the unit itself—cleaning, stripping, and readying it for burial and ventilation.

Make It Safe First: Decommissioning Refrigerants, Deep Cleaning, and Prepping the Box for Burial

Make It Safe First: Decommissioning Refrigerants, Deep Cleaning, and Prepping the Box for Burial

You found a dead chest freezer on marketplace, hauled it home, and you’re picturing jars of carrots tucked inside by first frost. Good. Before it becomes a root cellar, it has to stop being an appliance. Safety and stewardship come first—protecting people, the land, and your project.

Refrigerants: Decommission the Right Way

- Identify the refrigerant on the data plate (usually on the back or inside the lid). Older units may use R‑12 (ozone-depleting), many use R‑134a, and newer ones sometimes use R‑600a (isobutane, flammable).

- Do not cut lines or vent refrigerant. Besides being dangerous, it’s illegal in many places (e.g., U.S. EPA Section 608). Call a certified HVAC tech or a municipal recycling program to recover the refrigerant and oil. They’ll typically evacuate and tag it “empty,” often for a modest fee.

- If the unit is R‑600a, keep it outdoors and well-ventilated until decommissioned. No sparks, no smoking.

Why this matters: Proper recovery prevents injuries, protects creation from unnecessary emissions, and keeps your project above board.

Strip the Appliance and De‑energize

- Unplug and remove the power cord entirely. Capacitors can retain charge; treat the compressor box as live until it’s been safely disconnected and removed. If you’re not confident, have the tech or an appliance shop handle it.

- After recovery, unbolt and remove the compressor, condenser coils, and any exposed wiring to reduce weight (often 20–40 lb). Use a tubing cutter, not a saw, to avoid tearing the liner. Save the hinged lid and gasket.

- Dispose of components at an e‑waste or metal recycler. Wear gloves; old sheet metal edges are unforgiving.

Deep Clean and Deodorize

- Remove baskets, light housings, and the lid gasket. Wash the interior and gasket with warm water and mild detergent. Avoid strong bleach on metal—corrosion follows.

- Deodorize with a baking‑soda wash (1 cup per gallon warm water). For stubborn odors or mildew, spray 3% hydrogen peroxide, let sit 10 minutes, then rinse and dry.

- Sun-dry the open box for a few hours; UV and airflow do wonders. Reinstall the gasket after wiping it with a dab of food-grade mineral oil to restore flexibility.

Weatherproof and Prep for Burial

- Inspect for rust. Wire-brush, then prime with a rust-inhibiting primer. Seal any penetrations (where lines and wires used to pass) with marine epoxy or polyurethane sealant.

- Brush on two coats of bituminous foundation coating or exterior asphalt emulsion on the outside shell (not the interior). Let cure fully; this slows corrosion and moisture ingress underground.

- Remove child-safety latches. Plan for a secure hasp you can lock from the outside later; freezers can be suffocation hazards.

Common mistakes: Venting refrigerant; leaving latches intact; using harsh bleach that accelerates rust; failing to seal line holes, which invites groundwater into your carrots.

Key takeaway: Make it safe, clean, and sealed now so you can bury it with confidence. Next, we’ll choose a site and handle drainage so the “cellar” stays cool, not soggy.

Ground-Coupled Cooling Done Right: Excavation, Drainage, Anchoring, and Insulation Upgrades

Ground-Coupled Cooling Done Right: Excavation, Drainage, Anchoring, and Insulation Upgrades

A hard rain the night after you set the freezer in the hole will teach you two things fast: water finds the lowest point, and an empty freezer floats like a boat. Ground-coupled cooling works beautifully when you respect the soil, the water table, and physics. Do it right and you get quiet, steady 45–55°F storage with zero energy. Skimp and you’ll battle mud, mildew, and a freezer that “heaves” every spring.

Excavation: Depth, Clearance, and Base

Aim to bury the cabinet so its floor sits at or just below local frost depth (often 30–48 inches in temperate zones). That’s where soil temperature stabilizes near your annual average. Excavate a pit that gives 6–8 inches of clearance on all sides and 8 inches beneath the unit. Level the base and lay 6–8 inches of clean, washed 3/4-inch gravel. The gravel decouples the cabinet from seasonal surface temperature swings and promotes drainage without clogging. Keep the cabinet level front-to-back and side-to-side; a 1-degree tilt can cause doors to bind and pooling condensation.

Common mistake: digging just large enough for the freezer. You need space for drainage stone, perimeter pipe, and side protection.

Drainage That Actually Drains

Surround the base with a ring of 4-inch perforated drainpipe (holes down), sloped 1% (1/8 inch per foot) to daylight. No downhill outlet? Tie the ring to a sump: a 12–18-inch diameter perforated barrel or culvert section set 12 inches deeper than the base. Wrap gravel and pipe in nonwoven geotextile to stop silt. Against the pit walls, install a dimple drain mat or geotextile before backfill to keep fines off the cabinet and create a capillary break.

Troubleshooting: standing water in the sump after storms means your outlet is too high or the fabric clogged. Jet the pipe, then add a leaf screen and cleanout at the high end.

Anchoring: Beat Buoyancy Before It Beats You

A mid-size chest freezer displaces roughly 18–20 cubic feet of soil; in a saturated event that’s up to 1,200+ pounds of uplift. Anchor it. Two reliable options:

– Slab: Pour a 4-inch reinforced concrete pad 6 inches larger than the footprint. Set stainless eye-bolts in the slab and strap the cabinet down with two ratchet straps (front-to-back), using corner protectors.

– Earth anchors: Four helical anchors (30–48 inches) rated 500+ lb each at the corners, tied over the cabinet with webbing.

Never screw fasteners into the cabinet shell; you’ll create rust points and potential moisture ingress. Keeping it loaded also helps—but don’t rely on potatoes to fight physics.

Insulation Upgrades for True Ground-Coupling

You want the sides and bottom to “feel” the deep-soil temperature while shielding the top and shallow soils from seasonal heat and frost. Practical mix:

– Lid and “neck”: Add 2–4 inches of rigid XPS or polyiso to the lid and any collar/entry hatch. Seal with weatherstripping to stop warm, moist air intrusion.

– Upper sides: Add 1 inch of rigid foam on the top 12–18 inches of sidewall before backfill to block summer heat and winter frost from shallow soil. Leave the deeper sides and base uninsulated for coupling.

– Protection: Cover exposed foam with cement board or treated plywood to deter rodents. Use foam-safe adhesive and tape seams.

Avoid spray foams with heavy odors; they can linger in food storage. If you notice condensation on interior walls, increase lid insulation and check for air leaks before insulating deeper sides.

Key Takeaway: Build on rock, not sand—good drainage, solid anchoring, and smart insulation give you stable, ground-powered cooling. Next, we’ll dial in airflow and humidity management so the cellar keeps produce crisp without waste.

Breathe Easy Without Power: Passive Vent Design, Humidity Control, and Mold Prevention

A cold snap blows in overnight, and by mid-morning your breath fogs as you check the buried chest freezer. The thermometer reads 38°F—perfect—but the lid’s sweating and the potatoes feel clammy. This is where the cellar’s “lungs” matter. A passive vent system keeps air sweet, humidity right, and mold at bay—no wires, just simple physics and attentive stewardship of the harvest you worked hard to raise.

The Passive Draft That Does the Work

Create a gentle chimney effect with two vents: a low inlet and a high outlet on opposite ends. Drill a 1.5-inch inlet hole 2 inches above the interior floor; add a short PVC stub, insect screen (1/8-inch hardware cloth plus fine mesh), and an outside 90-degree elbow pointing down to shed rain. For the outlet, drill a 2-inch hole high on the opposite wall or lid, attach a vertical riser (18–36 inches above grade) with a rain cap. The larger outlet (about 1.8x the inlet area) reduces resistance and improves draft. Paint exposed pipe light color to reduce solar heating and midday backflow. Fit both vents with adjustable dampers—rubber test plugs or sliding baffles—so you can throttle airflow during deep cold to prevent over-drying or freezing.

Why it works: cool, dense air enters low, warms slightly off stored produce, rises, and exits high, carrying off CO2 and ethylene that age food. Keep the outlet shaded for a steadier pull.

Humidity: High Enough for Roots, Not for Rot

Aim for 90–95% RH for potatoes, carrots, beets, and cabbage; onions/garlic prefer 60–70% and do best in a separate bin with its own small vent or closed container. If RH dips below target (common in mid-winter), reduce vent opening and add moisture: a pan of water, damp burlap, or root vegetables nested in damp sand/sawdust. If RH creeps over 95% and condensation forms, open vents briefly during the coldest part of the day; outside air is drier in absolute moisture and will strip excess humidity.

Keep Mold at Bay: Cleanliness, Separation, and Surfaces

Start clean: wipe interior with 1 cup borax per gallon warm water, or 50/50 vinegar-water; let dry. Line shelves with slatted wood or perforated crates for airflow. Cure crops properly before storage (e.g., potatoes 50–60°F, high RH for 10–14 days) to toughen skins. Keep apples away from potatoes—ethylene from apples hastens sprouting. Remove any soft or damaged produce immediately; one bad carrot evangelizes mold faster than you can pray it away.

Troubleshooting Quick Hits

- Condensation on lid: improve weatherstripping, lengthen outlet riser, check damper balance.

- Musty smell: open dampers, clean with borax, cull suspect produce.

- RH swings daily: insulate exposed vent pipe and shade the outlet.

- Read the room: use a remote thermohygrometer; salt-test it annually for accuracy.

Key takeaway: let the cellar breathe with a sized, adjustable two-vent system, keep humidity in the sweet spot for each crop, and practice diligent housekeeping. Next up, we’ll map shelving and bin layouts to keep varieties separate, accessible, and long-lasting.

Stock It Like a Pro: Curing, Packing, and Ethylene-Smart Organization for a Season-Long Harvest

Stock It Like a Pro: Curing, Packing, and Ethylene-Smart Organization for a Season-Long Harvest

You’ve built the cellar; now the harvest needs to carry you through winter. Picture a cool October evening: bins of potatoes and carrots on the porch, onions braided and clacking, a heaping crate of apples perfuming the air. This is where stewardship and skill meet—curing, packing, and organizing so that every calorie you grew serves your family well.

Cure First, Store Second

Curing heals minor nicks, thickens skins, and extends shelf life. Skipping it is the fastest way to lose a season’s work.

– Potatoes: 50–60°F, 85–95% RH, 10–14 days, dark. Lay in shallow crates under a burlap drape in a garage or shed.

– Winter squash (not acorn): 80–85°F, 80–85% RH, 10–14 days. A warm room works; rotate for even airflow.

– Sweet potatoes: 80–85°F, 85–90% RH, 4–10 days, then store at 55–60°F.

– Onions and garlic: Warm, dry, airy space (70–80°F), 2–4 weeks until necks seal; then clip and mesh-bag.

Why it matters: Curing closes wounds and reduces rot vectors. If your chest freezer cellar runs cool and humid, do the curing elsewhere first; don’t try to cure inside—it’s the wrong climate.

Troubleshooting: If skins wrinkle, humidity was too low—use damp burlap next time. If mold appears, you had stagnant air—spread layers thinner and increase airflow.

Pack for Humidity and Breathability

In a chest freezer cellar, the bottom runs coolest and most humid; the upper third is slightly warmer and drier. Use that gradient.

– Roots (carrots, beets, parsnips): Layer in totes with damp (not wet) sand, sawdust, or peat. Aim for 90–95% RH inside the tote. Example: An 18-gallon tote holds ~40–50 lb of carrots with ~30–40 lb of medium sand. Vent lid with six 1/4-inch holes.

– Cabbage: Trim outer leaves, wrap heads in newspaper, stack on a slatted rack low in the chest.

– Potatoes: Crate or burlap sack, low in the chest, completely dark. Target 38–42°F. Never wash—just brush dirt.

– Onions/garlic: Mesh bags hung near the top—prefer 60–70% RH and good airflow.

– Winter squash: Single layer on a shelf or milk crates in the upper half, 50–55°F zone.

Common mistakes: Washing produce, packing too tightly, and stacking heavy bins that crush lower layers. Label every container with variety and date; rotate “first in, first out.”

Ethylene-Smart Organization

Ethylene-producing fruits (apples, ripe pears, tomatoes) accelerate sprouting and bitterness in ethylene-sensitive crops (potatoes, carrots, brassicas). Keep producers contained and vented.

– Keep apples in a lidded crate with small vents, placed high and toward your exhaust/vent side of the chest. Check weekly and remove bruisers.

– Store potatoes and carrots low and on the intake/cooler side, away from apple off-gassing.

– Greens, celery, and cabbages are ethylene-sensitive—wrap or place in separate totes with minimal crossflow.

Add-ons: Ethylene absorber sachets (permanganate/zeolite) or a “Bluapple”-style absorber in the apple crate can stretch storage life by weeks.

Troubleshooting: If carrots taste “soapy” or bitter, they’ve been exposed to ethylene—relocate apples or tighten lids. If potatoes sprout early, drop their temperature a couple degrees and increase separation.

Key takeaway: Cure appropriately, match each crop to its microclimate in the freezer, and treat ethylene like a gas you can route—producers up and vented, sensitives down and sealed. Next, we’ll talk inspection routines and spring cleanout so your system stays faithful through the long haul.

Built to Serve Through Winters: Monitoring, Maintenance, Troubleshooting, and Community Stewardship

A week after the first hard freeze, you slip out at dawn, lift the insulated lid, and watch a breath of cool, earthy air drift up. Your hygrometer reads 36°F and 92% RH—right in the sweet spot. That kind of steady winter service doesn’t happen by accident. It takes light-touch monitoring, simple maintenance, and a mindset that this little cellar can serve more than just your household.

Monitor the Microclimate

- Targets: For most roots (potatoes, carrots, beets), aim for 34–40°F with 85–95% relative humidity. Apples prefer 30–35°F and 90–95% RH; onions and garlic store better around 32–40°F but drier (60–70% RH).

- Tools: Use a max/min thermometer-hygrometer with a remote probe. Mount one probe mid-level near the center crate, and a second near the lid to catch stratification. Log weekly readings.

- Adjustments: If temps dip below 32°F, slide the upper vent closed to half, add two 1-gallon jugs of water for thermal mass, and lay a folded wool blanket over the lid. If temps creep above 45°F during a warm spell, open vents fully at night, shade the lid by day, and remove excess mass until a cold front returns. For low humidity (<80%), add a shallow tote of damp sand or drape damp burlap on a rack (not touching produce). For condensation or RH >96%, vent more for a day and set in a shallow tray of dry sawdust or wood ash to absorb moisture.

Simple, Regular Maintenance

- Monthly: Inspect lid weatherstripping; replace cracked foam with 1/2-inch EPDM or closed-cell tape. Check vent screens (1/8-inch hardware cloth) for rodent damage. Brush dust from vent tubes to keep passive airflow.

- Quarterly or between crops: Wipe the liner with 1:10 vinegar-water or 1 cup bleach per gallon of water; rinse and dry. Rotate bins so air channels (2 inches) remain along walls. Keep apples separated from potatoes to reduce sprouting (ethylene management).

Troubleshooting: Fast Fixes That Work

- Condensation dripping from the lid: Add a 1-inch foam board under the lid to interrupt the cold bridge; tilt the freezer 1/4 inch toward the drain side to direct drips to a gravel sump.

- Frost rime near vents: Fit a longer elbow or an external hood to cut wind-driven cold. Close the upper vent to 25% during arctic blasts.

- Off smells or sudden rot: Remove spoiled items immediately, sanitize spot, and reduce humidity for 24 hours. Review your bins—tight plastic smothers; perforated crates breathe.

- Sprouting potatoes: Too warm or near apples. Drop to 38–40°F and separate by a sealed tote.

- Slugs/ants: Copper tape around the lip deters slugs; a light ring of diatomaceous earth near vents helps ants—keep it off food surfaces.

Stewardship and Shared Resilience

Post a simple inventory and log sheet inside the lid. If you have surplus, invite a neighbor to store their late-season carrots or swap apples for onions. A cellar is more stable when opened less often; coordinate one weekly “harvest hour.” It’s a small act of stewardship—care for what you’ve been given, and let it bless others. In lean winters, that kind of fellowship multiplies warmth.

Key takeaways: measure, don’t guess; adjust vents before problems grow; sanitize regularly; separate incompatible crops; and consider your root cellar a community asset. Built right and tended simply, your freezer-turned-cellar will serve faithfully, season after season.

You’ve got everything you need to turn a dead box into a season-long pantry: a safe, decommissioned shell; earth-coupled temperature; passive lungs that breathe; and a storage plan that respects the quirks of each crop. The through-line is simple—control water, guide air, and let the ground do the cooling. Done right, you’ll trade utility bills for quiet, dependable storage that stretches your harvest and your budget.

Start moving: walk your site and mark a slightly elevated spot with natural drainage. Call a certified tech to recover refrigerant if that’s not already done. Inventory materials—washed 3/4-inch gravel, perforated drain tile, vapor barrier, rigid foam, PVC for vents, stainless mesh, silicone, and a hygrometer/data logger. Sketch your vent heights and run lengths to harness stack effect; plan anchoring so frost or buoyancy can’t heave the box. Put a weekend on the calendar and recruit a couple of strong backs—neighbors who help dig tend to share in the bounty.

When you stock it, cure roots properly, separate ethylene producers from sensitive crops, and track humidity like it matters—because it does. Keep a simple log: temps, RH, mold checks, gasket condition. Adjust vents with the seasons and don’t ignore condensation.

This is stewardship in action: taking what was broken and making it useful for your household and, if need be, for your community. Build it once, keep it honest with small habits, and let this quiet cellar carry your table—and maybe your neighbor’s—through the lean months.